You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Plasma Cosmology - Woo or not

- Thread starter Reality Check

- Start date

Reality Check

Penultimate Amazing

You do not need complex mathematics. Assume something charges up Mercury and then the math is easy. Of course if you want to waste you time then go ahead and do it. You will find that you are many orders of magnitude off the required values as has been pointed out to you.DD wrote

10 x 1012V sounds a lot is it? where'd that figure come from?

I gave fairly good description in post 2282 even had a crack at some maths, but which variables shall we use in which equation since Peeks Law was more to do with corona discharge on a wire inside the Earths atmosphere.

We want one for a sphere in a plasma stream.

ben m's original "back of envelope" calculation was DD's source of the ten tera volt source figure.

(Added emphasis specially for Sol88)

I will play along with the troll for a second.

Sol88, if you hypothesize that the planet Mercury was once charged up---like a great big capacitor---and that a runaway *discharge* created an arc, and the arc was responsible for the spider-like formation in the Caloris basin ... well, let's do some MATH.

Let's hypothesize that we can charge Mercury up. Just plug in a big jumper cable, or shoot a highly-charged wind at it, or ... something. One way or another, we'll hypothesize that we can build up an electrostatic voltage on the whole planet. How much excess charge can we pack on while doing this?

As an isolated sphere, Mercury's capacitance is about 0.2 millifarads. That's, um, not very much. A *gigavolt* static potential would carry only 200,000 Coulombs (about one car battery). I want to emphasize that a gigavolt is a very, very high potential. There is no way to charge something up to a gigavolt by bathing it in a kilovolt-energy solar wind.

Let's see, how much *energy* do you store when you pack 200,000 C into a gigavolt potential? 2 x 10^14 joules ... about 50 kT of TNT, or something in the ballpark of the Nagasaki atomic bomb.

Therefore, we have (unfortunately) lots of experience with the craters formed by 50 kT energy releases. They're a 100 meters in diameter and a few meters deep---underground explosions might excavate only a hundred meter or so cavity. Moving rock around takes lots of energy.

So what do we find on Mercury? A hole 40,000 meters in diameter.

Sol88, your "arc welder" hypothesis requires energy to be stored somewhere. The largest charge we can expect Mercury to pick up from the Solar Wind is a few kilovolts, giving it a few hundred Joules of energy---whereupon your Giant Arc Discharge Into Space could perhaps occur, but it would barely heat up a cup of tea, much less excavate a 40,000 meter crater.

How much energy do you think you need for the crater, Sol88? How will you charge up an isolated capacitor to the (apparently required) ten teravolts? You can't. Since Mercury could never have been this highly charged, it's never had anything like enough stored electrostatic energy to excavate a crater with an arc discharge. You casually invented an Giant Cosmic Welding Torch, Sol88, but you forgot to find somewhere to plug it in.

You're welcome to do the same calculation under the (equally stupid) assumption that Mercury had (like Earth) a dielectric atmosphere with an internal mechanical charge conveyor. You will have to learn electrostatics to do so.

Reality Check

Penultimate Amazing

This is obvious even for you Sol88: To answer the questions!So why are we still searching for answers to standard cosmology's questions.

There are several remaining questions, e.g.

- What is the composition of dark matter?

- What is the composition of dark energy?

- BBT is a factor of 2 out with the abundance of lithium. Is this a problem with BBT or the model used to predict the formation of Li in stars?

tusenfem

Illuminator

- Joined

- May 27, 2008

- Messages

- 3,306

Hmm, we have coherent sentences, no spelling errors, logical progression of thoughts -- this must be a ghost writer!

Not so:

"test" should be "tests"

"phenomena" should be "phenomenon"

but still, impressive by Sol88 standards

sol invictus

Philosopher

- Joined

- Oct 21, 2007

- Messages

- 8,613

So how that going? Standard cosmology I mean.

Extraordinarily well. Cosmology is in its golden age - tons of extremely accurate data, rapid narrowing of the cosmological parameter space... for the first time in history there really is a precise standard model of cosmology, and it fits observations very well.

Because you already know what powers galaxies

"Powers galaxies"? What on earth is that supposed to mean - they're not light bulbs, you know. If you meant stars, yes, that's very well understood.

you already know what makes galaxies rotate

Newton and Galileo knew that, 400 years ago. Apparently some people haven't heard the news about Newton's laws yet.

you already know whats makes them collide/merge

Same as above.

you already know how black holes/pulsars/neutron stars/magnatars are formed

Not entirely, but pretty much. And that doesn't have much to do with cosmology.

you already know what powers an AGN

Again with "powers". But yes, and the level of precision is improving very rapidly these days.

So why are we still searching for answers to standard cosmology's questions.

That's a question only you can answer...

Just dot the I's and cross the T's and publish a book for the next generation to know that's how it works.

Already done - many times over.

So what where we talking about again?

Beats me!

Oh yeah, that's right charge separation, magnetic fields, electric currents, electric fields, charged particle acceleration and conducting medium (plasma(99.999% of all observable matter in the universe is in the plasma state).

Right - all sorts of stuff that has nothing to do with cosmology.

What does the above list have in common with cosmology? wake up man!!

What are you talking about?

Belz...

Fiend God

Can we see the surface of Jupiter now?

I call ********!

Your ignorance is apalling.

That you use it as an argument is amusing.

Belz...

Fiend God

Eot-Wash experiments have been falsified by the pioneer effect!

Black Holes are a mathematical construct.

Dark matter is a hypothetical mathematical construct.

Dark energy is a hypothetical form of energy.

How can someone with so little knowledge of layman-level physics possibly claim to know more than the experts in the field ?

Ignorance breeds confidence.

Belz...

Fiend God

I am not a mathematician by a long shot! And maths is no substitute for common sense!

Why, yes. Yes it is a good substitute for common sense because common sense is what we USED to use to explain the universe and it got us gods and witches.

Belz...

Fiend God

Anaconda wrote

But it's just so much fun, watching them blindly follow and regurgitate the standard party line!

Well it's a good thing you're foregoing those evil mathematical equations and skipping straight to the common sense, eh ?

The pictures ARE the data

Just like conspiracy theorists.

Where are you getting your numbers from?

Did you happen to read these papers? Or are you still looking for your wall socket to plug you electrical cord in?

I take you do understand what induced means in this context? Magnetic induction

INDUCED MAGNETIC FIELD EFFECTS AT PLANET MERCURY

You did NOT present an "induction" hypothesis for crater formation. You posted a bunch of photos of voltage-driven, low-magnetic-field electric arcs.

If you want to throw away that hypothesis, it's fine with me, but that's what you proposed and that's all that I see in your "Mercury looks like Y" photos. That was your hypothesis (as far as you had thought it out), now you recognize that it's a stupid hypothesis.

Now that we've got that out of the way, please do not forget yourself and repost a bunch of pictures of welding arcs, discharge sparks, etc., since they have nothing to do with your hypothesis any more.

Moving on to your new hypothesis: "the Spider Crater on Mercury represents the discharge of some sort of magnetic induction effect" This is, sorry to say, even stupider. Why don't you draw us a diagram showing just one example of a variable magnetic field---from what source? With what direction? Changing in what direction and with what time dependence?---which, to your best understanding of the vector equation [latex]\nabla \times \vec{E} = \partial\vec{B}/\partial t[/latex], would generate fields appropriate for a 10^14 Joule discharge. Take your time and think about it.

(Or perhaps you don't want to think about it, you just want to assume that eventually you'll find some Web page somewhere with the words "electromagnetic" and "Mercury" in it, and that's all you need to do to topple mainstream science.)

DeiRenDopa

Master Poster

- Joined

- Feb 25, 2008

- Messages

- 2,582

but, but, ... ben m:

a) he did not even recognise that E and B were in bold (considerably earlier, when I was still trying to engage in a discussion with him), much less understood that it made a difference (not to mention why)

b) he has no idea what a vector is, much less what a vector equation is

c) you missed his post, quoted by Belz, where he declares that you don't need no equations (common sense is all you need)

d) but worst of all, ben m, you have no pictures in your post! not even a smilie!

not even a smilie!

a) he did not even recognise that E and B were in bold (considerably earlier, when I was still trying to engage in a discussion with him), much less understood that it made a difference (not to mention why)

b) he has no idea what a vector is, much less what a vector equation is

c) you missed his post, quoted by Belz, where he declares that you don't need no equations (common sense is all you need)

d) but worst of all, ben m, you have no pictures in your post!

not even a smilie!

not even a smilie!

sol invictus

Philosopher

- Joined

- Oct 21, 2007

- Messages

- 8,613

So, how do Clowe et al get from what was actually indicated to what they claimed? Only though a big assumption, which is in no way supported by their data.

The major assumption is that all of the baryonic, ordinary matter is in the form of hot plasma or bright stars in galaxies.

So 99% of the matter in the universe is NOT in plasma?!???!!???

What an admission from a PC/EU advocate!

What's unique and amazing about your post is that you're actually almost right. As you point out, the main conclusion we can draw from the Bullet cluster observations by themselves is merely that very little of the mass in those clusters is in plasma.

Of course when you throw in everything else we know from other observations, it's highly unlikely that the excess matter is baryonic (there just aren't any good baryonic candidates) - which is why they weren't very careful with the wording in their paper.

Last edited:

Tim Thompson

Muse

- Joined

- Dec 2, 2008

- Messages

- 969

I have looked at the earlier posts, though I admit in a less than completely rigorous fashion. I think I have seen enough of everyone's posts, here and on other boards, to get the point.However, in your review of the early parts of this thread - I think you said you'd be undertaking such a review, right? - please pay attention to Z's posting style. ...

This turns out not to be much of an argument, and is in fact one that has already been addressed in the literature. It is, therefore, not an "assumption" at all, in the sense you mean, but rather a logical consequence of observation.The flaw in this argument is this assumption that all the ordinary matter in galaxies is in easily-visible, bright, stars. Instead, most of the mass of galaxies may well be in the form of dwarf stars, which produce very little light per unit mass, in other words have a very high mass-to-light ratio. Several studies of galaxies using very long exposures have shown that they have 'red halos', halos of stars that are mostly red dwarfs. Other studies have indicated that the halos may be filled with white dwarfs, the dead remains of burnt-out stars. In addition, there is evidence that a huge amount of mass may be tied up in relatively cool clouds of plasma that do not radiate much x-ray radiation, and would be in closer proximity to the galaxies than the hot plasma.

First, let me address the case of the Milky Way in particular. We can't see it from outside, but of course we are a lot closer to the stellar halo of our own Galaxy than we are to the halo of any other galaxy. The advent of the Hubble Space Telescope has made it possible to search for read dwarf stars directly in the Milky Way halo, which could not be previously done from the ground. The result is that there are far too few red dwarf stars in the Galactic halo to account for the gravitational requirements that lead to the assumption of dark matter (see, i.e. Hubble Rules Out a Leading Explanation for Dark Matter, press release & images dated 17 October 1994). And see the paper The stellar halo of the Galaxy; Amina Helmi, The Astronomy and Astrophysics Review 15(3): 145-188, June 2008. This paper reviews the stellar halo of the Milky Way in detail, and includes a comment on gravitational microlensing that is relevant & important:

For example, if a significant fraction of the dark matter had been baryonic (composed by MACHO's, Paczynski 1986), then the stellar and dark halos would presumably be indistinguishable. However, this scenario appears unlikely, as the microlensing surveys are unable to assign more than 8% of the matter to compact dark objects (Tisserand et al. 2007, although see Alcock et al. 2000 for a different, though earlier result).

Now, let us consider the red halos that Zeuzzz refers to, supporting his claim that these halos could represent most or all of the dark matter as baryonic mass. To begin with, note the result already established above for our own Milky Way. If we make the not so bold assumption that the Milky Way is not a special case as spiral galaxies go, then we would expect that the same should be true for other spiral galaxies, on average. Namely, they do not have significant baryonic halos in the form of compact objects. This already makes the assumption that this is indeed the case for the Bullet Cluster galaxies a reasonable one. However, see the paper Red Halos of Galaxies Reservoirs of Baryonic Dark Matter?, Zackrisson et al., May 2008, from the IAU symposium proceedings. The red halos are not just "faint", they are "extremely faint". Zibetti, White & Brinkman, 2004 had to stack scaled images of 1047 galaxies from the SDSS just to get reliable photometry for halos with surface brightness of about 30 magnitudes per square arcsecond. The multiband colors for their stacked halo look like the color of the halo found around NGC 5907. However, Yost et al., 2000 looked at NGC 5907 in the near infrared, 3.5 - 5 microns, and did not detect the halo at all. These observations pose significant problems for interpretation. The multiband colors are not consistent with a normal distribution of stellar masses, and require a population unusually rich in low mass stars. However, low mass stars should stand out well in the near infrared, so a literal interpretation of the failure to detect the halo of NGC 5907 in the near infrared would imply that the halo is not made of stars at all. In any case, that failure limits the baryonic mass fraction of the halo to about 15%, if it is in fact made up of red dwarf stars.

The upshot of all this is that observation places strong limits on the mass available in these red halos. Photometry, sensitive to red dwarf stars, and microlensing, sensitive to all compact objects, both clearly show that there is not enough mass in the halo to account for the mass required to explain the dark matter effect. And the difference is significant. So there is no "flaw in the assumption" of Clowe et al., so long as we are talking about compact objects.

As for the gas clouds, they too will not do the job. In a collision between galaxies, we expect individual stars to collide only rarely, if at all. Likewise, in a collision between galaxy clusters, we expect individual galaxies to collide only rarely. However, the intracluster gas should undergo significant collision, as shown in the Clowe et al. paper. If there are cold intracluster clouds, they will be heated by the collision and emit X-rays. Only small clouds tied to the galaxy might escape this fate. But those clouds must carry negligible mass. After all, Briggs, 2004 tells us "Neutral intergalactic clouds are so greatly out numbered by galaxies that their integral HI content is negligible in comparison to that contained in optically luminous galaxies." HI is neutral hydrogen. So here again, observation clearly implies that the dark matter cannot be made of HI clouds.

So the conclusion is that the argument put forward by Zeuzzz is not valid. The "flaw in the assumption" is imaginary and not real. The conclusion reached by Clowe et al. stands at least as a reasonable interpretation of the observations. However, as we see from the 193 citations (so far), there is considerable discussion of the interpretation of the Bullet Cluster collision. There are claims that modified gravity theories can still do away with dark matter, and explain the observations, but this remains controversial. This is a point worth noting. There are legitimate alternative explanations put forth for discussion, based on modified gravity theories. They are not conclusive, but they are scientifically valid exercises. However, Zeuzzz, and other alternative critics typical of this and other discussion groups, are far to dismissive and arrogant in their approach, and base their claims not on legitimate scientific grounds, but on simplistic knee-jerk reactions. Just a little research would have quickly shown the the alternative put forth by Zeuzzz has already been outdated by research that is in some cases many years old.

Sol88

Philosopher

- Joined

- Mar 23, 2009

- Messages

- 8,437

So the spider crater shall be swept under the carpet as just a little impact crater with some idiosyncrasies!

We'll (eventually) find the evidence that tells us it's an impact crater over laid on a graben system!

Not many people engaged in trying to understand what this feature is and means, RC had a crack, but unfortunately came up with even more outlandish claims than me! wOw!

Everyone else dodged the question? Or just waved it of as an impact crater and from some of the papers RC sent us a link for, they *(mainstream) have NOT been able to replicate the terraced walls, central peaks, flat floors, crater chains and ray/spider features of so many of the solar systems idiosyncratic crater system.

Surely smashing something into something else in the lab should be able to reproduce these effects! Even very large >1mt thermonuclear blast can not replicated these crater features??

Now a percentage of craters we see on planets/moons would be from impact as there are lots of "bits" out there, but I think these would look more like your stereotypical craters, such as:

Nuclear Blast Crater

Nuclear Blast Crater

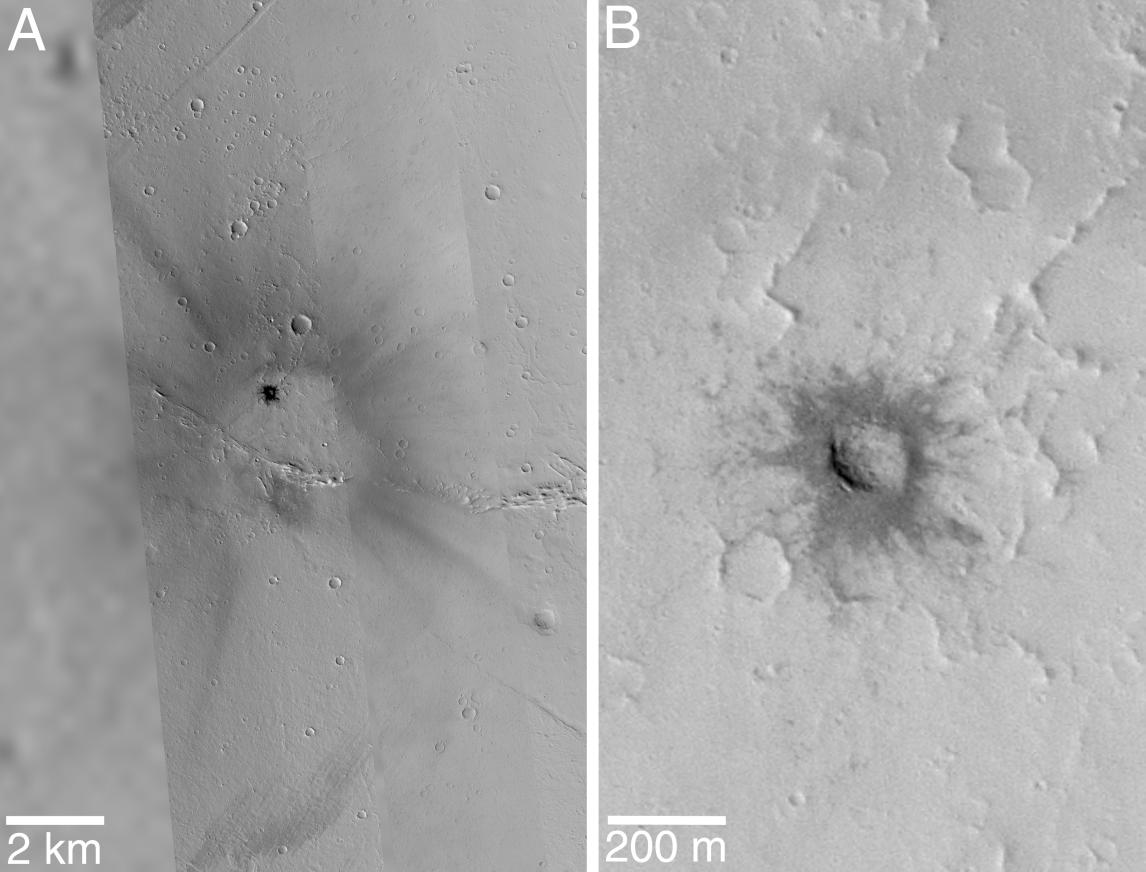

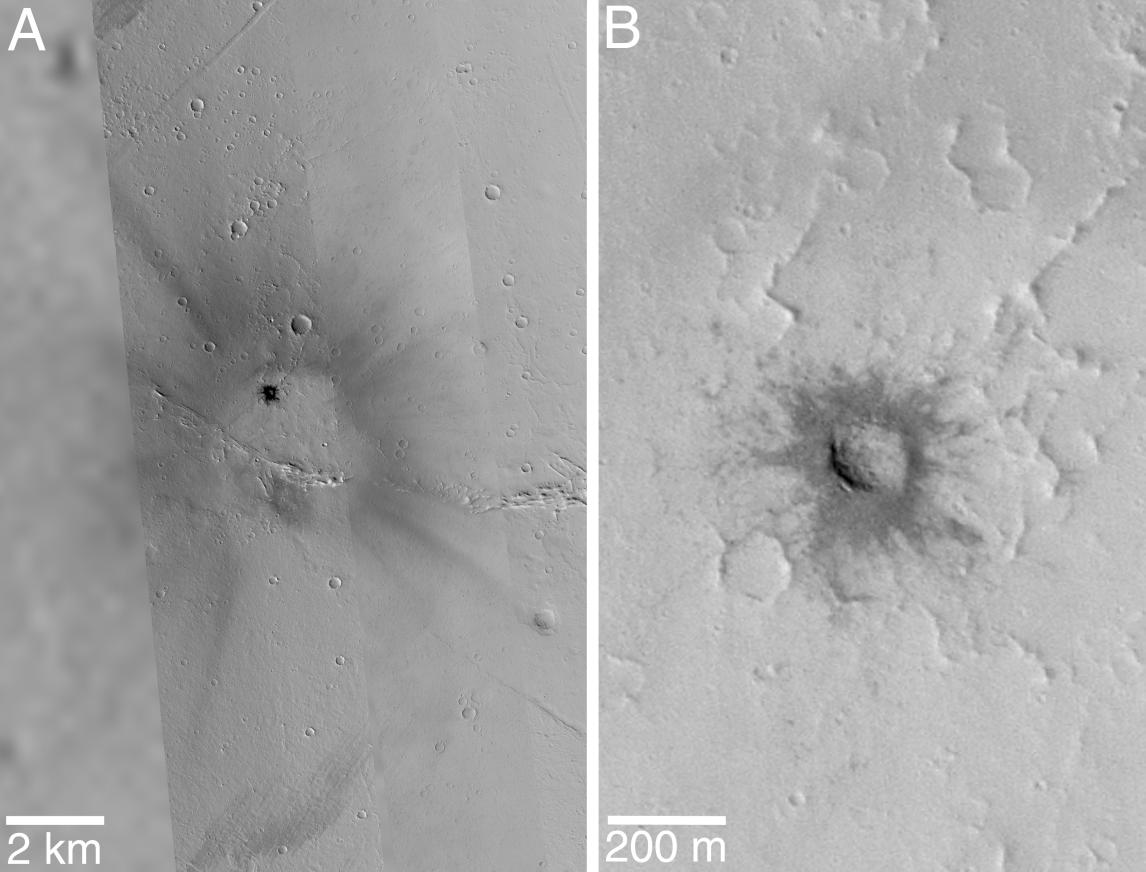

And one on Mars

I mean look at when they went a hunt'n for the impact crater here;

Image Credit:

Image Credit:

NASA/JPL/MSSS

LINK

Seems standard astronomers can not account for such different forms of "impact" craters found on so many bodies in the solar system, or at least no consistent explanation! why?

why?

If it's too hard just forget about it and move along eh? Is that scientific progress?

We'll (eventually) find the evidence that tells us it's an impact crater over laid on a graben system!

Not many people engaged in trying to understand what this feature is and means, RC had a crack, but unfortunately came up with even more outlandish claims than me! wOw!

Everyone else dodged the question? Or just waved it of as an impact crater and from some of the papers RC sent us a link for, they *(mainstream) have NOT been able to replicate the terraced walls, central peaks, flat floors, crater chains and ray/spider features of so many of the solar systems idiosyncratic crater system.

Surely smashing something into something else in the lab should be able to reproduce these effects! Even very large >1mt thermonuclear blast can not replicated these crater features??

Now a percentage of craters we see on planets/moons would be from impact as there are lots of "bits" out there, but I think these would look more like your stereotypical craters, such as:

And one on Mars

I mean look at when they went a hunt'n for the impact crater here;

NASA/JPL/MSSS

The picture on the left (above, A) is a mosaic of three MOC high resolution images and one much lower-resolution Viking image. From left to right, the images used in the mosaic are: Viking 1 516A55, MOC E05-01904, MOCM21-00272, and MOC M08-03697. Image E05-01904 is the one taken in June 2001 by pointing the spacecraft. It captured the impact crater responsible for the rays. A close-up of the crater, which is only 130 meters (427 ft) across, is shown on the right (above, B). This crater is only one-tenth the size of the famous Meteor Crater in northern Arizona.

The June 2001 MOC image reveals many surprises about this feature. For one, the crater is not located at the center of the bright area from which the dark rays radiate. The rays point to the center of this bright area, not the crater. Further, the dark material ejected from the crater--immediately adjacent to the crater rim in the picture on the right (above, B)--is not continuously connected to the larger pattern of rays. Asymmetries in crater form and ejecta patterns are generally believed to occur when the impact is oblique to the surface. The offset of the crater from the center of the rays suggests that the meteor struck at an angle, most likely from the bottom/lower right (south/southeast). The strange geometry of the rays is quite different from that seen for rays associated with impact craters on the Moon and other airless bodies; one possible explanation is that they resulted from disruption of dust on the martian surface by winds generated by the shock wave as the meteor plunged through the martian atmosphere before it struck the ground.

LINK

Seems standard astronomers can not account for such different forms of "impact" craters found on so many bodies in the solar system, or at least no consistent explanation!

If it's too hard just forget about it and move along eh? Is that scientific progress?

Tim Thompson

Muse

- Joined

- Dec 2, 2008

- Messages

- 969

Pantheon Fossae: Too Much to Handle?

Even if the statement were true, it would be irrelevant; it does not mean that your explanation must be, or even could be right. Indeed, while blathering away about Pantheon Fossae, you have ignored my response in Post 2267. Are you going to admit that I am too much for you to handle?Seems standard astronomers can not account for such different forms of "impact" craters found on so many bodies in the solar system, or at least no consistent explanation!

Ziggurat

Penultimate Amazing

- Joined

- Jun 19, 2003

- Messages

- 61,668

Surely smashing something into something else in the lab should be able to reproduce these effects! Even very large >1mt thermonuclear blast can not replicated these crater features??

Why would you expect it to? First off, that's small compared to the energy released in many asteroid collisions. Secondly, why would you expect an explosion and an impact to produce the same results? The energy transfer mechanisms aren't identical, nor are the ratios of energy to momentum.

You didn't source your picture (bad form), but it appears to come from the Sedan test. In this test, the bomb was detonated under ground. So even if we could use surface detonations of a bomb to simulate asteroid impacts (it's not clear that we can), it should be fairly obvious that subterranean detonations will not produce the same dynamics as a surface impact. So it's absolutely no surprise that the crater doesn't look like what you'd get from an asteroid impact. But I bet you never even stopped to consider whether this was a surface detonation or an underground one, did you?

Reality Check

Penultimate Amazing

I made no claims. I merely pointed out in my opinion that the image looked like 2 separate events due to the lack of craters in the spider crater compared to the surrounding terrain. These could be 2 impact events or something else. My amateur guess: A volcanic area created by the formation of the Caloris Basin with a recent impact crater in the center.So the spider crater shall be swept under the carpet as just a little impact crater with some idiosyncrasies!

We'll (eventually) find the evidence that tells us it's an impact crater over laid on a graben system!

Not many people engaged in trying to understand what this feature is and means, RC had a crack, but unfortunately came up with even more outlandish claims than me! wOw!

It is definitely not a graben system which is a depressed block of land bordered by parallel faults.

Nothing could be more outlandish than your physically impossible claim that you based on the fallacy that if something looks like somtheing else than it must be that.

"so many"Everyone else dodged the question? Or just waved it of as an impact crater and from some of the papers RC sent us a link for, they *(mainstream) have NOT been able to replicate the terraced walls, central peaks, flat floors, crater chains and ray/spider features of so many of the solar systems idiosyncratic crater system.

Is that 1, 100, 1000 or 1000000000 craters that cannot be explained (yet)?

I never posted any links to papers. But I do know (but from memories of distant astronomy classes) that "the terraced walls, central peaks, flat floors, crater chains and ray/spider features of so many of the solar systems idiosyncratic crater system" have been replicated. The exception is the 1 "spider feature" that you are obsessed with.

You have three (count them Sol88: 1, 2, 3) images. There have been 1000's of craters that have been imaged and are not idiosyncratic.

Let see: Millions of impact craters in the solar system. 1000's of them have been photographed and explained. You have a few that scientists are not sure about.Seems standard astronomers can not account for such different forms of "impact" craters found on so many bodies in the solar system, or at least no consistent explanation! why?

If it's too hard just forget about it and move along eh? Is that scientific progress?

Guess what - that is science (investigating the unknown). Learn to live with it!

Do you want to get back to plasma cosmology sometime (maybe this century

Reality Check

Penultimate Amazing

My guess is that you stopped reading the linked page when you got something that fitted your preconceived idea and missed the actual explanation.

LINKThe June 2001 MOC image reveals many surprises about this feature. For one, the crater is not located at the center of the bright area from which the dark rays radiate. The rays point to the center of this bright area, not the crater. Further, the dark material ejected from the crater--immediately adjacent to the crater rim in the picture on the right (above, B)--is not continuously connected to the larger pattern of rays. Asymmetries in crater form and ejecta patterns are generally believed to occur when the impact is oblique to the surface. The offset of the crater from the center of the rays suggests that the meteor struck at an angle, most likely from the bottom/lower right (south/southeast). The strange geometry of the rays is quite different from that seen for rays associated with impact craters on the Moon and other airless bodies; one possible explanation is that they resulted from disruption of dust on the martian surface by winds generated by the shock wave as the meteor plunged through the martian atmosphere before it struck the ground.

Sol88

Philosopher

- Joined

- Mar 23, 2009

- Messages

- 8,437

Even if the statement were true, it would be irrelevant; it does not mean that your explanation must be, or even could be right. Indeed, while blathering away about Pantheon Fossae, you have ignored my response in Post 2267. Are you going to admit that I am too much for you to handle?

no I did not!

You said in post 2267

Why the geological explanation should not be rejected

1) The Apollodorus crater is entirely consistent with impact crater shapes, both from physical models, and from laboratory experiments modeling impact features. There is no reason to reject this as an impact feature.

2) The assumption of pre-existing extensional stress in Caloris Basin is consistent with the observed presence of circumferential graben in the outer Caloris Basin, and is consistent with extensional stress in terrestrial basins.

3) The shape and pattern of channels in Caloris Basin is consistent with the geological interpretation that they are grabens.

4) There is no fundamental energy problem; the impact and pre-existing extensional stress provide all of the energy necessary to explain the work done in creating the grabens.

And RC wrote

I made no claims. I merely pointed out in my opinion that the image looked like 2 separate events due to the lack of craters in the spider crater compared to the surrounding terrain. These could be 2 impact events or something else. My amateur guess: A volcanic area created by the formation of the Caloris Basin with a recent impact crater in the center.

It is definitely not a graben system which is a depressed block of land bordered by parallel faults.

Whoo boy

They are! not wait there not...who knows!

The Man

Unbanned zombie poster

What does Reality Check's post have to do with you not responding to what Tim Thompson posted? Since you keep referring to RC are you the Richard Cranium of which you speak?