First, to address the back splatter of a bullet impact, this phenomenon is only observed when the target is something hard enough to resist the bulet for any reasonable time. This is most observable in the impact of the bullet or shotgun pellets against a steel target thicker than the sheet steel used in an automobile.

When a bullet with sufficient enrgy hits a steel target which does not yield immediately, both objects tend to melt partially. This is the reason that there will usually be a raised margin around the point of impact in the steel. The melting and deformation of the lead in the bullet cause the bronze jacket to split open. If you look closely at the debris that spreads out in the time that it takes for the steel to yield, you will see that the jacket tends to move laterally.

This can be compared easily to what happened at the Pentagon. The wall which the plane struck was utterly non-flexible, and had to be literally crushed by the impact. Bits of the fuselage and wings would, neccessarily, have shattered as does the jacket of a bullet striking a heavy steel plate. Thus, we have the little bits of sheet metal on the ground up-range of impact, while the heavier and denser parts, such as the longitudinal deck (to which the seats and nearly all really heavy internal structures, such as seats, are attached, continues on into the hole crushed by the weight of the aircraft.

But, if we examined the impact of a bullet with a paper target, we see that the paper yields almost immediately and does not even offer eenough resistance to deform the bullet in any manner. Thus, a bullet hole through a paper target will always have margins which are depressed on the impact side. (Trust me on this one. I have made enough holes in paper with various sorts of munitions that I can state categoricly that this always occurs barring the presence of a very sensitive explosive charge in either the projectile or target.)

Another interesting phenomenon occurs when the target is a milk jug full of water, or a watermelon or a human body. When a bullet enters a plastic jug of water, the water becomes pressurized and must escape. Generally, it does so out the exit hole down-range. Thus, the jug is propelled up-range while the water goes down-range.

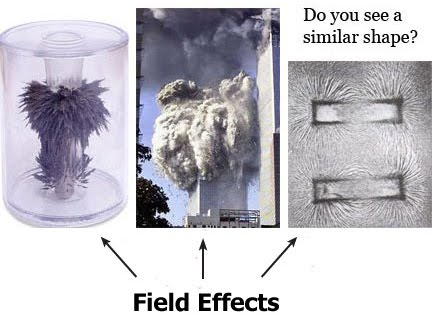

The walls at the WTC did not need to be crushed. They were just shoved in like the fibers of a paper target until the fibers (in this case the bolted-together perimeter columns) broke and bent inward, down-range.

The interiors of the towers were briefly over-pressurized and a shock wave was established inside the buillding, but that shock wave and over-pressurization did not rebound significantly out the entry hole until, apparently, deflagration of the fuel started inside the building. Thus we see windows popping out parallel to the neccessary path of the shock wave, releasing pressurized fuel vapors and air, and the cloud of fuel vapor and the fireball are significantly larger down-range, out the other side of the building, and the denser materials that ade it that far, such as at least one engine and a landing gear, continue down-range. There is no reason for there to have been any back-splatter because the towers behaved more in the manner of a paper target than in that of a steel plate or brick wall.

Duuuuh!

Duuuuh!