Here are NIST's conclusion for WTC1.

I've copied them for you directly from NCSTAR1-6D, Chapter 5, pg. 313-314.

I've numbered each.

Now you can take each of your observations and tell us: "This observation negates NIST's claim(s) A13 & C4 because …"

And then explain clearly & precisely why, of course.

___

Aircraft Impact

A1. The aircraft impacted WTC 1 at the north wall.

A2. The aircraft severed or heavily damaged Columns 112 to 151 between Floors 94 and 98 on the north wall.

A3. After breaching the building’s perimeter, the aircraft continued to penetrate into the building.

A4. The north office area floor system sustained severe structural damage between Columns 112 and 145 at Floors 94 to 98.

A5. Core Columns 503, 504, 505, 506, 604, 704, 706, 805, and 904 were severed or heavily damaged between Floor 92 and Floor 97.

A6. The aircraft also severed a single exterior panel at the center of the south wall from Columns 329 to 331 between Floor 93 and Floor 96.

A7. In summary, 38 of 59 columns of the north wall, three of 59 columns of the south wall, and nine of 47 core columns were severed or heavily damaged.

A8. In addition, thermal insulation on floor framing and columns was also damaged from the impact area to the south perimeter wall, primarily through the center of WTC 1 and over one-third to one-half of the core width.

A9. Figures 2–2, 2–14, and 2– 18 summarize aircraft impact damage to exterior and core columns and floors of WTC 1.

A10. Gravity loads in the columns that were severed were redistributed, mostly to the neighboring columns.

A11. Due to the severe impact damage to the north wall, the wall section above the impact zone moved downward as shown in Figs. 4–9 and 4–13.

A12. The hat truss resisted the downward movement of the north wall and rotated about its east-west axis, which reduced the load on the south wall.

A13. As a result, the north and south walls each carried about 7 percent less gravity loads at Floor 98 after impact, the east and west walls each carried about 7 percent more loads, and the core carried about 1 percent more gravity loads at Floor 98 after impact (Table 5–3).

A14. Column 705 buckled, and Columns 605 and 804 showed minor buckling.

Unloading of Core

B1. Temperatures in the core area rose quickly, and thermal expansion of the core was greater than the thermal expansion of the exterior walls in early stages of the fire.

B2. This increased the gravity loads in the core columns until 10 min after impact (Table 5–3).

B3. The additional gravity loads from adjacent severed columns and high temperatures caused high plastic and creep strains to develop in the core columns in early stages of the fire.

B4. More columns buckled inelastically due to high temperatures.

B5. Creep strain continued to increase to the point of collapse (see Fig. 4–81).

B6. By 30 min, the plastic-plus-creep strains exceeded thermal expansion strains.

B7. Due to high plastic and creep strains and inelastic buckling of core columns, the core columns shortened, and the core displaced downward.

B8. At 100 min, the downward displacement of the core at Floor 99 became 2.0 in. on the average, as shown in Fig. 4–37.

B9. The shortening of core columns was resisted by the hat truss, which unloaded the core over time and redistributed the gravity loads from the core to the exterior walls, as can be seen in Table 5–3.

B10. As a result, the north, east, south, and west walls at Floor 98 carried about 12 percent, 27 percent, 10 percent, and 22 percent more gravity loads, respectively, at 80 min than the state after the impact, and the core carried about 20 percent less loads as shown in Table 5–3.

B11. The net increase in the total column load on the south wall, where exterior wall failure initiated, was only about 10 percent due to the downward displacement of the core (see Fig. 5–3).

B12. At 80 min, the total core column loads reached their maximum.

B13. As the floor pulled in starting at 80 min on in the south side, the south exterior wall began to shed load to adjacent walls and the core.

Sagging of Floors and Floor/Wall Disconnections

C1. The long-span trusses of Floor 95 through Floor 99 sagged due to high temperatures.

C2. While the fires were on the north side and the floors on the north side sagged first, the fires later reached the south side, and the floors on the south side sagged.

C3. Figure 5–4 shows vertical displacements of Floors 95 through 98 determined by the full floor models at 100 min.

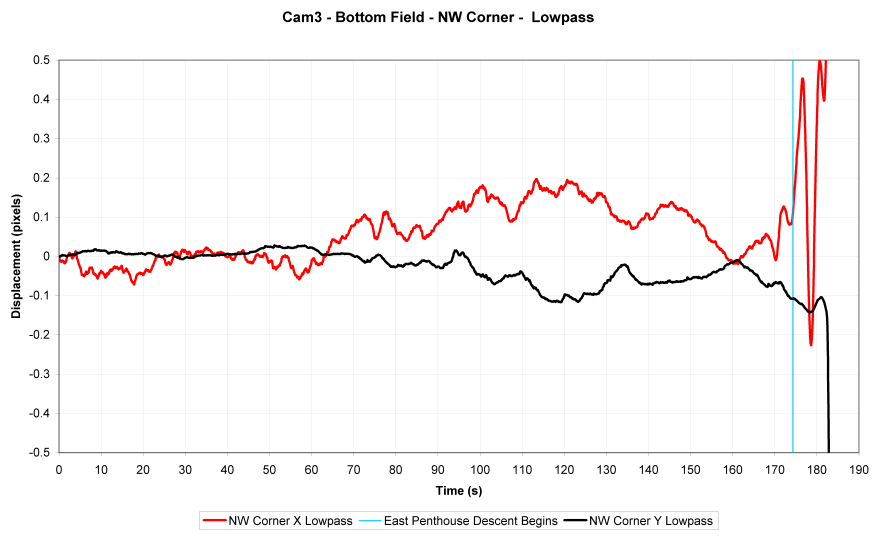

C4. Full floor models underestimated the extent of sagging because cracking and spalling of concrete and creep in steel under high temperatures were not included in the floor models, and because the extent of insulation damage was conservatively estimated.

C5. The sagging floors pulled in the south wall columns over Floors 95 to 99.

C6. In addition, the exterior seats on the south wall in the hot zone of Floors 97 and 98 began to fail due to their reduced vertical shear capacity at around 80 min, and by 100 min about 20 percent of the exterior seats on the south wall of Floors 97 and 98 failed, as shown in Figs. 5–4 and 5–5.

C7. Partial collapse of the floor may have occurred at Floors 97 and 98, resulting from the exterior seat failures, as indicated by the observed smoke puff at 92 min (10:19 a.m.) in Table 5–2, but this phenomenon was not modeled.

Bowing of South Wall

D1. The exterior columns on the south wall bowed inward as they were subjected to high temperatures, pull-in forces from the floors beginning at 80 min, and additional gravity loads redistributed from the core.

D2. Figure 5–6 shows the observed and the estimated inward bowing of the south wall at 97 min after impact (10:23 a.m.).

D3. Since no bowing was observed on the south wall at 69 min (9:55 a.m.), as shown in Table 5–2, it is estimated that the south wall began to bow inward at around 80 min when the floors on the south side began to substantially sag.

D4. The inward bowing of the south wall increased with time due to continuing floor sagging and increased temperatures on the south wall as shown in Figs. 4–42 and 5–7.

D5. At 97 min (10:23 a.m.), the maximum bowing observed was about 55 in. (see Fig. 5–6).

Buckling of South Wall and Collapse Initiation

E1. With continuously increased bowing, as more columns buckled, the entire width of the south wall buckled inward.

E2. Instability started at the center of the south wall and rapidly progressed horizontally toward the sides.

E3. As a result of the buckling of the south wall, the south wall significantly unloaded (Fig. 5–3), redistributing its load to the softened core through the hat truss and to the south side of the east and west walls through the spandrels.

E4. The onset of this load redistribution can be found in the total column loads in the WTC 1 global model at 100 min in the bottom line of Table 5–3.

E5. At 100 min, the north, east, and west walls at Floor 98 carried about 7 percent, 35 percent, and 30 percent more gravity loads than the state after impact, and the south wall and the core carried about 7 percent and 20 percent less loads, respectively.

E6. The section of the building above the impact zone tilted to the south (observed at about 8 ̊, Table 5–2) as column instability progressed rapidly from the south wall to the adjacent east and west walls (see Fig. 5–8), resulting in increased gravity load on the core columns.

E7. The release of potential energy due to downward movement of building mass above the buckled columns exceeded the strain energy that could be absorbed by the structure.

E8. Global collapse ensued.