Evolution gave us our values. Brain structure and physiology give us our values.

Evolution and physiology give us the morals we have about prostitution, drug use, etc?

Many people obtain those values from religion. Science? Not that I know of.

Religion is merely one of many modifiers of those values.

Well, what do you mean by that? Do you mean that there are natural values and morals and religion just perverts these?

If you disagree then please tell us, how do values get magically installed in one's thoughts and at what age does this occur?

I believe our values are constantly changing and one of the major purposes of religion is to give us grounding values to base our lives on.

Science? Not that I know of.

Wowbagger said:

It was, afterall, the science of anthropology that was demonstrating that all races of humans really are "created" equal, an therefore deserve and equal opportunity to freedoms and responsabilities, etc. Religion never did that.

Pfff, evidence?

Perhaps I shall forget about the Quakers?

Anyone in full possession of the facts would agree, it is time for that to be put right; few, if any, deserve greater credit for the defeat of slavery and the slave trade than them. The campaign to abolish the slave trade was an overwhelmingly religious affair. The importance of evangelical Anglicans, like William Wilberforce and John Newton, is well known.

But Quakers were the pioneers of the movement, its brains, and much of the soul too. The more you delve into the story, the more you find Quakers under every shadow.

...

The Quakers were natural enemies of slavery, with their fundamental belief in equality in a hierarchical society where that was still highly controversial. They believed above all else that every person is made in the image of God and carries the divine light, so it is blasphemous to elevate one above another.

They refused to raise their hats to their social betters or to call them "my lord", "my lady" or even "you", insisting on the familiar "thou". Their egalitarianism was still quite scandalous in the 18th Century, but it made slavery uniquely abhorrent to the Quakers.

Linky.

The abolitionist and women's suffrage movement in America were also propelled by religious people. I don't recall reading about anthropology in Sojourner Truth's speeches.

FireGarden said:

I'm willing to give up on the infallibilty aspect, then.

Why do some Buddhists believe in reincarnation and some not? What would convince a Buddhist to change his opinion on reincarnation?

Oh, rebirth is a very messy issue. First there is the very strong cultural influence that various regions had about reincarnation before Buddhism came. And add to that the various disagreements about the exact nature of "not-self". Because the Buddha said there was no soul, there is a lot of confusion about what would actually pass on in rebirth.

And, though this might get too specific, in Buddhism one of the "sins", if you will, is clinging to doctrine. The Right View aspect of Buddhism also includes on a deeper level the idea that

all views are wrong views.

Anyway, I'm sure I've just confused you more than answering your question

.

What changes scientific opinion is rather plain and obvious: a better idea to explain observed facts. I feel I understand that kind of thinking.

But religious thinking is a mystery to me. Reinterpreting evidence/sacred texts/traditions. When something in religion does change, I find it hard to understand why. It's like changing fashions.

Why is it okay to open shops on the Sabbath now? When did Gods become all knowing?

The history of religion doesn't build to anything. The history of science does

Yes, I quite agree here. Which I think leads to another difference between the two.

That is, religion pertains to Absolute Truths about reality. Science is about using empiricism to develop models ever approaching the accurate depiction of the universe.

h.g.Whiz said:

Religion imposes why, and science proposes how.

I still disagree with this view that there is some distinct alien entity, like "Islam", that slips into people's minds and leads them astray. For any ideas that a person encounters, it is up to them to choose how they respond to them. And they choose how they develop them.

Sure, many are indoctrinated or evangelized. But that is not a universal trait for religion.

JoeTheJuggler said:

Inquisition, Crusades, Jihad, religious fanatics flying airplanes into skyscrapers, suicide bombers, the Creationists' believing their lies in the Dover case were justified, many of the ethical laws put forth in holy scriptures, etc.

Well, I would say that those are instances of religion working very well on giving morals

. They don't necessarily have to be "good" ones.

You misread me then. I think the capacity for morality is nearly universal (there are sociopaths and such), just as the capacity for language is universal. The variation of the languages a human can learn is relatively small (Pinker has it down to a small handful of switches that can go one way or another). Similarly, the actual moral principles we can internalize aren't really very diverse.

What I think is bogus is claiming that religion is the sole source of these principles, and that science has nothing (and will never have anything) to say about morality and ethics.

Ah, well I think morals are a tad more diverse than what you think, and I don't think religion is the sole source, so we are pretty much in agreement.

And I agree that science can help in applied ethics, but I disagree that it has anything to say about guiding values.

I assume you mean you "really

can't see" this.

And there was a time when people couldn't see how science could possibly say anything about human origins. Give the track record of the ever-shrinking realm of stuff that is exclusively the bailiwick of religion, I think it's arrogant to presume that the gaps that remain will always remain.

But science is about objective empiricism and is completely descriptive. Morality is proscriptive.

I don't think of it as a gap for science, I think they are to parallel planes.

OK--now you're speaking the language of the OP. Couldn't you say that one of the major points of religion is also to make models of reality?

Except that with religion, there is no concern of testing those models against reality (i.e. the models aren't based on evidence). Again, I reject the notion that religion is defined by a certain content area (values, morality or whatever) because it most certainly has not been for most of its history. Also, at least some branches of science are making inroads into those topics. (You could certainly talk about "how to live your life" as having to do with behavior. Also studies of neuroscience and cognition can study MANY questions related to these topics.)

Well, we'll have to just disagree here. Religion has no concern about "testing the models against reality" in an objective empirical sense. Many religious people have their own way of testing the teachings that don't involve double blind studies

.

KeyserSoze said:

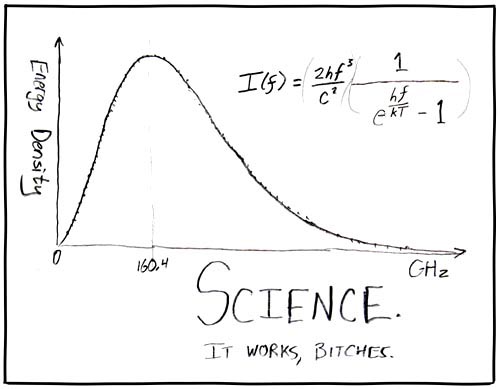

This is not my summary, but it is definitely my favorite.

http://img160.imageshack.us/img160/2...3271193wa2.png

See, I think this is the problem with this discussion. I don't think this sums up the difference at all because it only shows where religion conflicts with the empirical, scientific realm.

The people I talk to are not strawmen, however, and they hardly talk about creationism or any of that stuff.

Also, I think it highlights the ethnocentrism with everyone defining religion by what they know of the Abrahamic faiths (No matter how incomplete I think that knowledge is).