You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

HopDavid

Thinker

- Joined

- Feb 17, 2011

- Messages

- 193

Groovy, thanks for expanding my understanding.

You're welcome. And thank you for a gracious response.

RobRoy

Not A Mormon

You're welcome. And thank you for a gracious response.

No worries. If I'm wrong, I'm wrong. That much water on the moon's surface actually reduces the concerns of habitation. Not colonization, per se, but certainly setting up some kind of fixed, and resupplied station. A first effort of mining that ice and bringing it into a beachhead would be a major accomplishment. Recycling and reusing the water would create a semi-sustainable outpost. Nothing close to colonization, but much more feasible than I had first thought.

Lamuella

Master Poster

- Joined

- Mar 29, 2006

- Messages

- 2,480

You could colonize the moon easier than Mars. The moon has a lot of frozen water and its closer to earth than mars. Like Mars youd have to live most of your life indoors except on rare occassions when you suit up.

not only is the moon closer, but it's always pretty close to the same distance from us, hence you don't have to worry as much about accessibility windows.

I suppose the most vital need of any moon base would be power. What with it being in space and all and efficient fusion still not possible, solar should work well enough. Does the moon have correct resources to manufacture some form of solar cell locally?

I suspect HopDavid can answer that question, but I think the answer is yes (sorry, in a rush, no time to research). But at least initially the best solution is likely nuclear power.

Once you've got your solar cell manufacturing in place, then solar may become more attractive.

Something I was thinking about recently: the cost of getting some of those valuable asteroids into earth orbit is mostly in the delta v. All the "mining asteroid" schemes seem to requires a large expenditure of energy to get the materials here (either mine first then bring it over, or park the thing in orbit and mine it here). But just altering it's orbit a little isn't anywhere near as energy intensive.

So, here's a "use the moon" idea: alter the orbit of a high value asteroid such that it impacts the moon. We've not used the moon's orbital velocity to "move the asteroid" into earth orbit. Mind you it's in a few more pieces than before. Now, go to the moon and "mine" the impact site.

The question is, how much of that material of the original asteroid will remain localized at least close to the impact site, such that mining might be feasible? Will it just vaporize and spread out over the entire surface, or will a sizable amount fall back near the impact site such that there will be very high concentrations of the original material?

So, here's a "use the moon" idea: alter the orbit of a high value asteroid such that it impacts the moon. We've not used the moon's orbital velocity to "move the asteroid" into earth orbit. Mind you it's in a few more pieces than before. Now, go to the moon and "mine" the impact site.

The question is, how much of that material of the original asteroid will remain localized at least close to the impact site, such that mining might be feasible? Will it just vaporize and spread out over the entire surface, or will a sizable amount fall back near the impact site such that there will be very high concentrations of the original material?

ConspiRaider

Writer of Nothingnesses

- Joined

- Dec 7, 2006

- Messages

- 11,156

Take a look at my signature and you'll get a clue as to how I feel about the Moon.

What we should have continued, after the mad dash to land - were missions to train ourselves on how to survive - for awhile - in an environment far removed from Little Blue Earth.

The Moon is perfect for that. Hostile enough for an ideal testbed - close enough to reach in days - safe enough to get folks home in a hurry, should the need arise. It doesn't get any better than this; if we proceed with my plan to get very familiar and comfortable within our solar system. We are going to need 'truck stops' all over the place once we truly get serious about plying the solar neighborhood. Whether those are on asteroids, Mars, planetary moons such as Callisto, Titan, Triton and so forth: We're going to need to plunk down for awhile for whatever: Refuel, replenish, rotate the crews/inhabitants on the truck stops and so forth.

The knowledge to travel regularly in space won't just 'come' to us. We have to go out and get it, implement it, test it, perfect it. That is what we use the Moon for. Not population offloading. That is a pure pipe dream.

What we should have continued, after the mad dash to land - were missions to train ourselves on how to survive - for awhile - in an environment far removed from Little Blue Earth.

The Moon is perfect for that. Hostile enough for an ideal testbed - close enough to reach in days - safe enough to get folks home in a hurry, should the need arise. It doesn't get any better than this; if we proceed with my plan to get very familiar and comfortable within our solar system. We are going to need 'truck stops' all over the place once we truly get serious about plying the solar neighborhood. Whether those are on asteroids, Mars, planetary moons such as Callisto, Titan, Triton and so forth: We're going to need to plunk down for awhile for whatever: Refuel, replenish, rotate the crews/inhabitants on the truck stops and so forth.

The knowledge to travel regularly in space won't just 'come' to us. We have to go out and get it, implement it, test it, perfect it. That is what we use the Moon for. Not population offloading. That is a pure pipe dream.

jasonpatterson

Philanthropic Misanthrope

Something I was thinking about recently: the cost of getting some of those valuable asteroids into earth orbit is mostly in the delta v. All the "mining asteroid" schemes seem to requires a large expenditure of energy to get the materials here (either mine first then bring it over, or park the thing in orbit and mine it here). But just altering it's orbit a little isn't anywhere near as energy intensive.

So, here's a "use the moon" idea: alter the orbit of a high value asteroid such that it impacts the moon. We've not used the moon's orbital velocity to "move the asteroid" into earth orbit. Mind you it's in a few more pieces than before. Now, go to the moon and "mine" the impact site.

The question is, how much of that material of the original asteroid will remain localized at least close to the impact site, such that mining might be feasible? Will it just vaporize and spread out over the entire surface, or will a sizable amount fall back near the impact site such that there will be very high concentrations of the original material?

It would depend strongly on the impact site, the relative velocities of the asteroid and the moon, and the size of the asteroid. A relatively small asteroid dropped at low velocity (relatively speaking, obviously) should stay fairly close to the impact site. That said, the craters of the moon were formed by asteroid impacts, there's no real need to cause additional impacts to check to see if the idea works, just check out the existing craters. If the scheme would work and the little green men haven't already gone through with their metal detectors and found the stuff, there is a lot smaller input cost to the plan.

One major downside to this is the added cost of removing the metal from the lunar surface and transporting it back to Earth (or even lunar orbit.) The cost to get from a NEO asteroid that is in the same plane as Earth back to Earth orbit is very small, energetically speaking.

I also like the idea of trying to move a metallic asteroid and a carbonaceous asteroid close together (or perhaps collide them at low velocity) so that half of an asteroid is converted into a mine and the other half living space. Unfortunately, at the moment we're having a hard enough time getting people into low earth orbit, let alone exploration and expansion.

Patrick1000

Banned

- Joined

- Jul 22, 2011

- Messages

- 3,039

Are you sure they could navigate across cislunar space.....

Are you sure they could navigate across cislunar space..?????...That's an awful long way to go without a compass....

Land is in short supply and life expectancy rates are climbing dramatically and will continue to do so with upcoming advances in biotechnologies and pharmaceuticals. Its time to discuss how we can expand and the moon is the closest. My first idea is simple, a biodome like structure planted permanently on the moon. We could even crash the iss into it for it if we really wanted but that was built so fast with international support i'm sure a moon base could be developed in ten or so years. Now a wacky idea I had for colonizing the moon involved melting both ice caps completely and turning the water vapor into breathable atmosphere. The goal of this is to extend the atmosphere of the Earth so far it wraps around the moon, what I believe is the only way to get the moon to hold a full atmosphere. I'm unsure of the distance to atmospheric expansion ratio but just thought we could also lower the sea level using some of the oceans to supplement this project and extend it enough. What are your ideas for the moon?

Are you sure they could navigate across cislunar space..?????...That's an awful long way to go without a compass....

India's lunar orbiter Chandrayaan-1 detected what seem to be sheets of ice at least two meters thick. See Nasa Radar finds ice deposits at Moon's North Pole.

The October 2010 issue of Science looked at LCROSS ejecta. It evidently contains 5.5% water as well as nitrogen and carbon compounds:

N 6.6000%

CO 5.7000%

H2O 5.5000%

Zn 3.1000%

V 2.4000%

Ca 1.6000%

Au 1.6000%

Mn 1.3000%

Hg 1.2000%

Co 1.0000%

H2S 0.9213%

Fe 0.5000%

Mg 0.4000%

NH3 0.3317%

Cl 0.2000%

SO2 0.1755%

C2H4 0.1716%

CO2 0.1194%

C 0.0900%

Sc 0.0900%

CH3OH 0.0853%S 0.0600%

B 0.0400%

P 0.0400%

CH4 0.0366%

O 0.0200%

Si 0.0200%

As 0.0200%

Al 0.0090%

OH 0.0017%

That gives a whole new perspective on moonshine!

The costs to simply lift a signficant portion of Earth's population into space, even if they did nothing other than die immediately*, would be staggering. And that's not even getting them into orbit, let alone to the Moon.

A few people have mentioned cost, but I don't think that's necessarily the biggest concern. More important is simply the number of people you would need to move. Let's assume that we've solved all the problems associated with building a lunar base and are ready to start shipping people out there. How many people do we need to move? Well, the current population growth rate is around 78 million people per year (134 births, 56 deaths). Deaths are expected to increase to 80 or so by 2040, so lets conservatively say the population is increasing by 50 million per year once we're ready to start shipping. That's 137,000 per day.

So, how many have we actually managed so far? According to Wiki, 529 people have travelled into space according to the USA definition. That's just over 10 per year, or 500,000 times too low. Of course, the vast majority of those never actually got anywhere near the Moon.

And how many could we actually mange? Let's use the shuttle as a baseline, although it was never actually capable of getting anywhere near the Moon (the highest was around 35,000 km for geostationary transfer, over 10 times too low). The shuttle can carry a maximum of about 25,000 kg, so call it around 250 people (it's around 1,000 m3, so should be big enough to fit them in, if rather cramped for a several day journey). That means something like 550 shuttle flights every single day. So far there have been a grand total of 135 shuttle flights in just under 30 years, split between 5 shuttles.

In other words, we would need, at an absolute minimum ignoring any need for servicing between flights, 88 times as many shuttles (4 day flight each way, so you need 8 times more than the 550) making 45,000 times as many flights. To put that in perspective, there have been a grand total of 6854 spacecraft ever launched. Just to keep the Earth's population constant, you'd need to launch more spacecraft every two weeks than humanity has managed in its entire history. And that's with incredibly unrealistic assumptions about what a shuttle can actually do, along with rather optimistic assumptions about how many people you need to move in the first place.

So yeah. Shipping people off the Earth != the answer.

I think you are underestimating how far away the moon is. Depending on where it is in its orbit, the moon is between 362,000 and 405,000 kilometres away from the Earth. To put that in perspective, that's about 30 times the diameter of the Earth.

To put that in even more perspective, Jupiter has a radius of just under 35,000 km. In other words, extending the Earth's atmosphere out to the Moon would require turning it into a gas giant over 10 times the radius (and therefore 1000 times the volume) of the largest planet in the solar system. To put it in even further perspective, the Sun has a radius of a bit under 700,000 km. Extending the Earth's atmosphere out to the Moon would require turning it into a star half the size (1/8 the volume and presumably mass) of the Sun. The smallest known star has a mass around 1/100 that of the Sun.

So forget all the stuff about drag and pressure. What's being proposed here is having the most of the population of Earth live inside a star, with the remainder merely living at its surface.

Edit: One other thing worth bearing in mind. The Moon's surface area is a bit under 40 million km2. Antarctica's surface area is around 14 million km2. The Sahara's area is about 10 million km2. Greenland is over 2 million. In fact, the Moon's entire surface area is only slightly larger than that of the Earth's 10 largest deserts combined. So if land is the problem, we already have plenty right here with virtually no-one living in it, and that is far easier to get to and far, far easier to make habitable.

Last edited:

alexi_drago

Graduate Poster

- Joined

- Oct 2, 2006

- Messages

- 1,353

Do the space elevator ideas actually have a chance of becoming reality? I don't mean for taking large numbers of people off earth but for getting large amounts of material to and from orbit cheaper than using rockets?

sts60

Illuminator

- Joined

- Jul 19, 2007

- Messages

- 4,107

Somewhere, maybe not in this thread, I believe someone mentioned dropping comets on the Moon to add to the water. (This was done on Venus in, IIRC, 2061 by Arthur C. Clarke.)

It would a fun exercise to figure out what it would take to terraform the Moon using comets and some sort of Barsoomian atmospheric plant which would constantly replenish the atmosphere. Assume you could build the space infrastructure to capture and place some sort of ion drives to round up the comets, and had all the power you needed to extract desired gases from lunar materials. How fast would you have to produce and replenish an atmosphere? What would be the desired mix of gases as you evolved the atmosphere to something thin but breathable?

It would a fun exercise to figure out what it would take to terraform the Moon using comets and some sort of Barsoomian atmospheric plant which would constantly replenish the atmosphere. Assume you could build the space infrastructure to capture and place some sort of ion drives to round up the comets, and had all the power you needed to extract desired gases from lunar materials. How fast would you have to produce and replenish an atmosphere? What would be the desired mix of gases as you evolved the atmosphere to something thin but breathable?

HopDavid

Thinker

- Joined

- Feb 17, 2011

- Messages

- 193

I suspect HopDavid can answer that question, but I think the answer is yes (sorry, in a rush, no time to research). But at least initially the best solution is likely nuclear power.

Once you've got your solar cell manufacturing in place, then solar may become more attractive.

The moon's hard vacuum, so vapor deposition is easier. This is the advantage Alex Ignatiev and other push for solar cell pavers.

One of the major obstacles (there are several) is feed stocks. Mining and purifying them takes energy and infrastructure.

In particular, mining aluminum is very energy intensive. You melt a halogen salt, dissolve alumina in the the molten salt and then separate the aluminum using electrolysis.

One of the major obstacles in my daydreams to split lunar water into propellant is the need for a robust power source. I've heard of solar cells that crank out 200 watts per kilogram. It takes about 286 kJ to crack a mole of water (about 18 grams). As you know, landing mass on the lunar surface is very difficult and expensive. Landing a power source able to crack propellant at a useful rate is rather implausible with present state of the art.

A power source up to mining aluminum and the other solar cell paver feed stocks is even less plausible.

So it's kind of a chicken and egg problem -- you need lots of power to make lunar solar cells from local materials. How do we get that first robust power source on the lunar surface?

HopDavid

Thinker

- Joined

- Feb 17, 2011

- Messages

- 193

Do the space elevator ideas actually have a chance of becoming reality? I don't mean for taking large numbers of people off earth but for getting large amounts of material to and from orbit cheaper than using rockets?

In my opinion no. At least not like the elevator from earth to geosynch and beyond as portrayed in Arthur C. Clarke's Fountains of Paradise.

Such a beanstalk would have a huge cross sectional area. Thus it is vulnerable to damage from space debris and micrometeorites.

Designs call for elevator cars climbing the stalk at 360 km/hour. At this rate it would take 4 or 5 days to reach geosynch. And how many elevator cars can a bean stalk support? You would need a through put rate that provides enough revenue to exceed elevator maintenance costs. This is discussed in The Space Elevator Feasibility Condition

So even if we did manage to manufacture carbon bucky tubes in long lengths as well as the political support for such an expensive mega engineering project, it's far from a given that an elevator would be the panacea some hope for.

An orbital space tether is somewhat more plausible.

Last edited:

The Greater Fool

Illuminator

In my opinion no. At least not like the elevator from earth to geosynch and beyond as portrayed in Arthur C. Clarke's Fountains of Paradise.

Such a beanstalk would have a huge cross sectional area. Thus it is vulnerable to damage from space debris and micrometeorites.

Designs call for elevator cars climbing the stalk at 360 km/hour. At this rate it would take 4 or 5 days to reach geosynch. And how many elevator cars can a bean stalk support? You would need a through put rate that provides enough revenue to exceed elevator maintenance costs. This is discussed in The Space Elevator Feasibility Condition

So even if we did manage to manufacture carbon bucky tubes in long lengths as well as the political support for such an expensive mega engineering project, it's far from a given that an elevator would be the panacea some hope for.

An orbital space tether is somewhat more plausible.

A space elevator is currently feasible for the Moon (and Mars), from what Wiki says:

Wiki said:A lunar space elevator can possibly be built with currently available technology about 50,000 kilometers (31,000 mi) long extending through the Earth-Moon L1 point from an anchor point near the center of the visible part of Earth's moon.[49] However, the lack of an atmosphere allows for other, perhaps better, alternatives to rockets, such as mass driver systems.

On the far side of the moon, a lunar space elevator would need to be very long (more than twice the length of an Earth elevator) but due to the low gravity of the Moon, can be made of existing engineering materials.[49]

Dumb All Over

A Little Ugly on the Side

I would take issue with your first stated premise. No, land is not in short supply.Land is in short supply....

HopDavid

Thinker

- Joined

- Feb 17, 2011

- Messages

- 193

Somewhere, maybe not in this thread, I believe someone mentioned dropping comets on the Moon to add to the water. (This was done on Venus in, IIRC, 2061 by Arthur C. Clarke.)

It would a fun exercise to figure out what it would take to terraform the Moon using comets and some sort of Barsoomian atmospheric plant which would constantly replenish the atmosphere. Assume you could build the space infrastructure to capture and place some sort of ion drives to round up the comets, and had all the power you needed to extract desired gases from lunar materials. How fast would you have to produce and replenish an atmosphere? What would be the desired mix of gases as you evolved the atmosphere to something thin but breathable?

Using comets to terraform Mars was used in Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars Trilogy. Chris McKay is also an advocate, see Technological Requirements for Terraforming Mars

Zubrin and McKay proposed comet impacts to vaporize the CO2 and water at the Martian poles. Once these green house gases are in the atmosphere they hope for runaway green house effect. Thus in their scheme, most of the atmosphere comes from volatiles already on Mars' surface. The volatiles from asteroids would add a small fraction.

They propose strapping four 5 gigawatt NTR rockets to bodies out past Saturn. To provide a reference, the largest U.S. power plant is the Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant in Arizona. This plant's 3 reactors put out 3.8 gigawatts.

So Zubrin & McKay's NTR rocket would need a power source six times as powerful as the largest nuclear power plant in the U.S. And they propose to put this rocket on an object in the outer solar system.

They propose to use the comet's mass as reaction mass. The cometary volatiles need to find their way to the rocket chamber. So in addition to a mammoth rocket and power source they would need to establish a mining and transportation infrastructure on this comet.

I believe terraforming any celestial body is a pipe dream. Inhabitants of Mars, moon or asteroids will live in wholly artificial environments probably buried in regolith.

Lack of atmosphere is a lunar advantage. It opens the possibility of mass drivers. Mass drivers could make a huge difference in reaction mass needed for exporting resources. I would not want an atmosphere on the moon.

HopDavid

Thinker

- Joined

- Feb 17, 2011

- Messages

- 193

A space elevator is currently feasible for the Moon (and Mars), from what Wiki says:

Yes, a moon and Mars elevator are more doable than an earth beanstalk.

But I differ with Wiki on some parts about the moon elevator. The closest thing to a moon synchronous orbit are the earth moon L1 and L2 points. EML1 is about 56,000 kilometers from the moon's surface. EML2 is about 63,000 kilometers from the moon's surface.

For all points between EML1 and the moon's surface, the net acceleration is towards the moon. So the tether would have to extend well beyond the EML1 to balance the moon's pull. So a 50,000 km tether extending from the moon's surface would fall back to the moon.

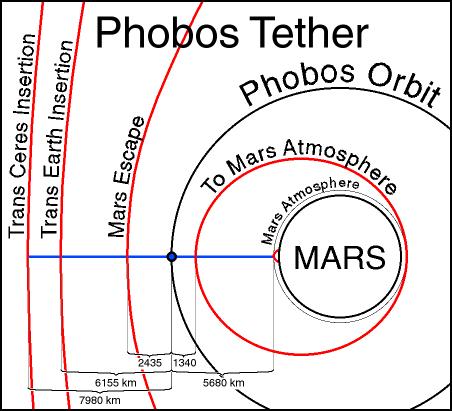

Favorable conditions for a beanstalk is high angular velocity and shallow gravity well. By those criteria, the best body I know of is Phobos. It's gravity well is negligible and, if I remember right, it's angular velocity is one revolution each 7 hours and 40 minutes.

The foot of the above tether is moving .6 km/s with regard to Mars. So rendezvous could be accomplished with small suborbital hops from Mars' surface. A lander entering Mars' atmosphere at .6 km/s would have much less Entry Descent and Landing (EDL) issues.

All of the above tether lies below Mars synchronous orbit (17,000 km altitude). A Mars beanstalk would have to extend well beyond Mars synchronous orbit.

Last edited: