Michael Mozina

Banned

- Joined

- Feb 10, 2009

- Messages

- 9,361

Wrong. The difference is that the umbra has a heat sink, empty space above it.

But that very same logic doesn't work for me and a Birkeland solar model because?

Wrong. The difference is that the umbra has a heat sink, empty space above it.

By the laws of physics, that 4000K umbra is not only "thermodynamically possible" - it is actually observed!By your same logic, that 4000K umbra is "thermodynamically impossible" too.

But that very same logic doesn't work for me and a Birkeland solar model because?

Asking how "all this energy" suddenly "cools off" is very poor wording from a physical perspective. The better-phrased question would be "why is the matter in the umbra cooler than the matter in the surrounding, brighter areas."

As previous posts have explained, the umbra is cut off from the convection cells that dominate the surrounding areas.

Thus, as the umbra radiates heat, it simply cools off because the matter in the umbra is not cycling back down to the deeper, hotter regions.

The density of the sun, computed from its gravity and diameter is about 1.4 g/cm**3.

The density of iron in the normal solid state is 7g/cm**3.

Simplifying greatly, an iron sun would weigh 5 times more than a gaseous one.

But really it would be much higher as the iron would be under such pressure at the center that in fact it would be a neutron star...

Of course there's still radiative and conductive heat transfer from below and from the surrounding areas.

And, of course, the umbra itself is still radiating. But since the conductive and radiative coupling to the rest of the sun transfers quite a bit less energy than convection, the umbra's equilbrium temperature (where its radiation is equal to the energy it's receiving from the rest of the sun) is quite a bit lower than the equilbrium temperature of the non-sunspot areas.

If you think that it's simply impossible for convection to be cut off like that, explain why.

If you think that cutting off convection couldn't cause the umbra's equilibrium temperature to be that much lower, I think you'll have to give us something quantitative rather than just asserting that this mechanism can't possibly give the observed result.

As for "it all suddenly cools off" - why do you think it's sudden?

Yes, it does. It just doesn't transfer heat as rapidly as convection does, so the sunspot's equilibrium temperature is lower.

ETA - I'll openly admit this is not one of my areas of expertise. Tim, Zig, Sol, RC, etc - I'm confident that you'll let me know if I got any of it wrong.

Fair enough.

How exactly is it "cut off" from the convection below, and what about the momentum of that updrafting heat?

http://solar-b.nao.ac.jp/QLmovies/movie_sirius/2009/12/31/FG_CAM20091231000109_235508.mpg

http://solar-b.nao.ac.jp/news/070321Flare/SOT_ca_061213flare_cl_lg.mpg

Ooops, posted too soon. I'll get to the rest in a second, but I have a hard time jiving that concept with the visual data. That orange images shows a filament winding its way down the umbra and the B/W image shows the effect over a larger area. It certainly appears as though material is cycling back into the umbra, not simply coming up through it.

But that very same logic doesn't work for me and a Birkeland solar model because?

It gets worse.

density of iron = 7850 kg/m3mass of sun = 1.99x1030 kg

outer diameter of sun = 1.39x109 meters

Using the outer diamter of the sun as an outer diamter for any iron shell, it is trivial to calculate that the thickness of this shell would have to be about 90 km in order to provide the gravity observed.

And that is assuming that the inside is hard vacuum. Add any mass in there (like, say, a heat soruce) and the thickness gets thinner.

Anybody want to calculate how much strength 90 km of iron has?

And how much stress and strain that shell would be under?

Anybody want to calculate how much strength 90 km of iron has?

And how much stress and strain that shell would be under?

Of course you know that your qualifications to understand solar imagery have been challenged

How exactly is it "cut off" from the convection below, and what about the momentum of that updrafting heat?

FYI, the shell isn't solid iron IMO, it's a standard volcanic 'crust' like the Earth, or like Mercury in terms of overall composition. It's probably more metallic than either the Earth or Mercury, but it's not likely to be made of solid iron IMO and it has "plasma pressure" inside the shell.Just an FYI....

Because in your model, the surface is completely surrounded by the photosphere, but in a sunspot, one side is exposed to (mostly) empty space.

How could you not have read the image caption?How can you be that close, and yet that far?Hi Tim Thompson, you may have been fooled by MM's ignorance of what the image contains.

Sunspots Revealed in Striking Detail by Supercomputers has the following caption for the image:

and from the animation page:

The image is of magnetic field strength, not convection.

It looks like MM has just looked at the image and said "looks like convection so must be convection" without bothering to even read the caption. What a surprise!

The field and the strength at that field are directly related to the "mass flow" inside the discharge loops that we see in the Hinode overlay image which come up along side (inside) the penumbral filaments. I've shown you the mass flow image movies in 171A, the Hinode CA/X-ray overlay images, tons of Hinode images galore, and you still don't seem willing to put two and two together. Yes, you're right, those are "magnetic fields" and that "magnetic field" is directly related to the "mass flow/current flow" coming up/down inside the loops and through the penumbral filaments. How can you not see that or the curvature *DOWN* in the Gband images?

Yes, you're right, those are "magnetic fields" and that "magnetic field" is directly related to the "mass flow/current flow" coming up/down inside the loops and through the penumbral filaments.

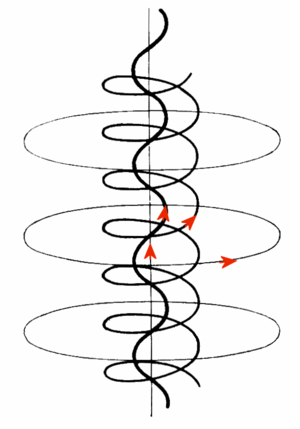

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birkeland_currentNo, Michael. The magnetic field at the center of those sunspots is vertical. Any current flow responsible for creating a vertical magnetic field must be horizontal. Basic electrodynamics fail.

Others will have to go into the specifics. My understanding is that strong magnetic fields prevent the plasma from rising into the sunspot area (plasma and magnetic fields have a thing going on), and that creates a region that's cut off from the 'normal' convective flows.

And, I don't want to be too pedantic, but "the momentum of that updrafting heat" doesn't make any physical sense.

Heat doesn't have momentum.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birkeland_current

No, it's called a Birkeland current, otherwise known as an ordinary current carrying filament like the one we see winding it's way down the umbra in that orange Hinode image, only much faster, and at higher energy state.