But neither me nor Ziggurat was; we were talking about measuring the red/blue shifts of the light from celestial objects and how they change over the course of the year. If light from different celestial objects were coming in at different speeds, the change in their red shifts and blue shifts over the course of the year would also be different. They aren't.

If the light is traveling through the atmosphere, it will be traveling at the speed of light in that medium.

In v = c - H * D, the c and H are constant. The D is distance.

----

The photon's distance from where it was emitted is crucial to keep in mind at all times. Consider light that has traveled billions of years to reach your telescope. The light enters the lens, gets focused to the eyepiece, and then into your eyeball.

Seems pretty straightforward. But at some level, some type of interaction with the light and the lens must be focusing the light. At the quantum level, the photon will have been absorbed by atoms in the lens. Then it is re-emitted (or an entirely new photon is emitted), and focused to your telescope's eyepiece.

The photon may have traveled great distances from its source before it encountered your telescope, but the light inside the telescope will be very close to its source: the lens that focused it. The distance to the source of the photons in the telescope will be less than a meter, not millions of light years.

In that case the refreshed photon will be traveling at c, which now results in an elongated wavelength when calculated.

Tests

Test 1: measure the speed of a cosmologically red-shifted photon

This is the first obvious test of the hypothesis.

But it would take thousands or millions of years to perform a fully controlled experiment where light is emitted with a known energy at a known time and travels across a known distance to see the effects of red-shift.

Using light that has already traveled millions of years seems to be the only choice.

But interacting with the photon will cause it to reset its distance and speed, as mentioned in the previous section. The task then is to come up with a clever way to measure the speed of ancient light without disturbing the photon.

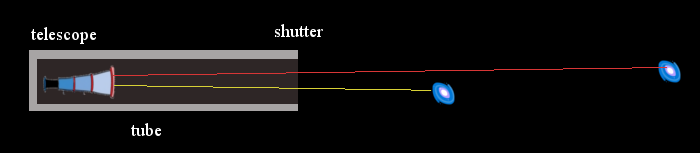

Consider a long tube in space with a telescope at one end and an open shutter at the other. The telescope has a nearby galaxy and a highly red-shifted galaxy in its sight.

What happens when the shutter is closed?

Prediction: Because the red light is moving slower than the yellow light, first the nearby galaxy will disappear from view, then the distant one.

Obviously the longer the tube is the better the experiment would be. A few kilometers at least, a light second would be great. If we use a predictable and fast enough object in space as the shutter, that might work just as well. The shutter must not reflect any light. The moon may be too bright and too slow to work.