Hi Oystein

Very interesting and visually clear comparison. I hope you have patience for my "beginner" questions.

1. Harrit's test shows twice the energy of thermite, right? I probably do not understand the concept of energy, but here goes: Is more energy not the same as "more powerful", meaning that Harrit's "nanothermite" is some sort of "superthermite"?

2. Is it possible to reach higher energy levels from a "normal" burning than a thermite reaction? I thought that a thermite reaction needed to be exceptionally energetic in order to melt steel or be used to weld steel. What am I missing here?

3. Both T&G and Harrit's experiment reach only temperatures far below the melting point of steel. How is that possible? Can you weld steel at temperatures lower than the melting point of iron? I always thought that thermite would reach temperatures in the thousands. Is the low temperature due to a very short time span of the experiment in the sense that we only see the beginning of the process? So if it were to continue the temperature would rise into the thousands?

Kind regards

Steen

Hi Steen,

ooh yeah, you are missing a lot, and it so happens it is what Harrit and Jones pretend to miss as well - except they are professors in the natural sciences and must be expected to know better, whereas you are not.

Where to begin?

First, the difference between "energy" and "power".

Energy is the potential to do "work". For example, If you have a lake and and a dam, and a turbine in the dam, then the lake stores a certain amount of "potential energy", by way of being filled to a certain hight with a certain mass of water. This energy is a constant number as long as the water content remains the same.

Now you can release the water through the turbine and do "work", for example grind coffee. Or, more conventionally, turn the potential energy to electrical energy, which does work elsewhere (heat coffee, run TVs...). You can release that energy slowly, by letting the water just trickle out of the lake, or rapidly, by rushing large amounts of water through. If you do is slowly, say it takes a month to empty the lake, "power" is low, and if you do it quickly, say, in a day, "power" is high.

So we learn: Power is how much energy you release in a given amount of time.

Now you could have two lakes: One stores twice the energy of the other, but still work at less power, because you release the water from the smaller lake faster.

It's the same with chemical reactions: If you have two reactions, one can release more energy, and the other more power, simply because one occurs faster than the other. For example, body fat a lot of energy, but you metabolize it slowly, and thus with relatively little power. This reaction of "burning" reaches only a temperature of <40 °C. If however you set fire to a glass of cask-strength rum, it will burn with a hot flame and with much more power.

Body fat contains 38 kJ of energy per gram (that's the energy density)

Cask-strength rum (56 vol-% ethanol) contains only about 15 kJ/g

So rum has less energy per gram, but more power per gram, when burned in the open, compared to fat metabolism.

Thermite has only 4 kJ/g.

Epoxy has 25 kJ/g

Wood has 18 kJ/g

Even your body, because if contains body fat and other energetic organic substances, such as meat, has, on average, around 8 kJ/g - even though it consists mostly of water!

These energy densities are maximum values - the best that can happen in theory, and it is physically impossible for these reactions to release more energy. It is possible though that they release less energy, for example because they don't run to completion (some fuel remains unburned, or oxidation isn't complete), or because your substance isn't pure and contains stuff that doesn't react.

(In fact, Harrit e.al. point out that their four test results differ because all four chips contained varying proportions of the gray layer, which is probably inert, or "dead weight")

So you see, thermite is actually one of the least "energetic" stuffs around.

BUT it can be more powerful - when you make it burn really fast, and that is much of the point of nano-thermite: Because the ingredients are so fine, they can react extremely fast, and release all their energy in a very short time. That is

part of the reason why (nano-) thermite gets so hot.

On the other hand, your thermite is spent after a very short time - and that's why it is total nonsense when truthers believe that thermite could explain why the debris piles were hot for weeks! Either thermite burns fast, then it could not heat stuff for weeks; or, if it burns for weeks, it burns with VERY little power, and is, at any rate, much worse at keeping the rubble hot than even burning human remains!

Another reason, the main reason actually, why thermite reaches extreme temperatures is that all its ingredients and, more importantly, it's reaction products, have high boiling points: Nothing turns to gas. When you burn organics (fat, epoxy, ethanol...), many reaction products are gasses. Gasses have a habit of rapidly taking away a lot of the energy that is released. Because increasing temperature is just one way that the chemical energy of a reaction does "work" - expanding volume is another, and those two targets for the energy to go to rival each other when gasses are created. So creating gasses tends to limit the temperature that is reached. This is no problem for thermite - the products, iron and aluminium oxide, turn to gas only at extreme temperatures, and so most of the energy release goes into heating them, and little into expanding them.

In the DSC experiment, temperature is tightly controlled. You usually have a probe that is tiny compared to the crucible it is places upon. It is difficult for the solid parts of the probe to attain a temperature much higher than that of the crucible it lays on. The DSC adds heat (energy, electric) to the crucible and measures the resulting temperature. When temperature rises because of a reaction on the crucible, the device feeds in less electrical energy, to keep the temperature rise constant at, say, 10 °C per minute. Through this temperature control, you also control reaction speed.

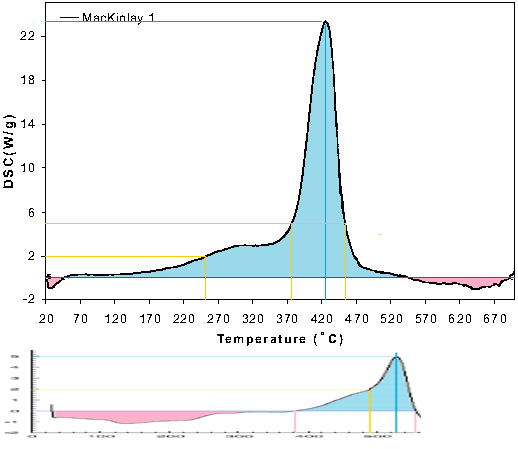

Harrit, farrer etc, like to claim that a narrow, steep peak in the DSC trace means a very rapid reaction, but that isn't true at all! Like I wrote in my earlier post: the peak that looks steep and dramatic from 380°C to approx. 455°C actually represents a reaction that tool 7.5 minutes! We are talking about tiny specimens that weigh much less than a microgram, and they react over the course of many many minutes in the DSC., In fact, heating it from 20°C to 700°C takes 68 minutes - more than an hour! Nothing is rapid there.

With all that said, now short answers:

1. No, more energy does not necessarily mean more "powerful". The power is dependent on haw fast the reaction occurs. It is correct though that you could "enhance" the energy content of a thermite preparation by mixing it with substances that have a higher energy density - for example organic substances. But once you find that most of the energy release must come from stuff other than thermite, you couldn't call the composite "thermitic in nature". Also, as organics release gas when heated, these composites are again limited in temperature - you couldn't melt steel with a composite that's, say, 70% organic and 20% thermite.

2. It's not the "energy" in thermite that enables it to reach extreme temperatures, but the fact that it burns rapidly and doesn't expand much as a gas - in other words, the energy it releases, although relatively low absolutely, is very concentrated in time and space, and thus, for a very short time and in a very limited volume, you get to melt steel.

3. The low temperature (up to 600-700 °C ) shown in the DSC results is mostly a property of the DSC device controlling temperature tightly, which in turn controls (to some extent) the speed at which reactions take place. Also, these temperatures are not how hot the reaction products get, but how hot the DSC device makes the crucible.

In "the wild", the same reaction could reach a higher, or a lower, temperature than the DSC does. Also, it may run much faster "in the wild" than in that controlled environment.

T&G by the way point out explicitly that the DSC profile cannot be taken as an indication for reaction speed, and that other types of experiment would have to be done to measure that.