But in the Driver, et. al. paper, they show a lot of the energy excess in the UV band.

Does it? Where? I'm looking at figure 4 and I see the data points (purple, SDSS/Galex) lying right on top of the model (orange) in the UV.

But in the Driver, et. al. paper, they show a lot of the energy excess in the UV band.

Does it? Where? I'm looking at figure 4 and I see the data points (purple, SDSS/Galex) lying right on top of the model (orange) in the UV.

The excess UV is in the greyed area to the left of Figure 4.

If I understand correctly, if the total cosmic spectral energy distribution is different than what has been assumed, then the distribution of stellar types may have to be revised.

It seems that the changes to aggregate mass won't change my much, however.

Some of which ben_m has already said ...I will have more to say later ...

And a point I have also made ...The inferred amount of dust-obscured UV is consistent ("in excellent agreement") with the observed amount of reheating of this dust---in other words, the light has been there and observed for a long time, so this correction does not change your estimate of the galaxy's luminosity---it only changes your estimate of how much of that luminosity comes from bluer stars.

Also note that they are talking about starlight, that is light directly produced by stars. Astronomers already knew long before this 2008 study that starlight is absorbed by dust and the energy re-radiated in longer wavelength infrared photons. So astronomers have long used the infrared luminosity of a galaxy as a tracer for star formation rates. The photons do not directly escape the galaxy as starlight, but the energy does escape, as longer wavelength infrared photons produced by the dust in response to absorbing starlight (the photons that did not escape). So that baryonic mass is in fact already accounted for in the form of a star formation rate, rather than in the form of existing stars. So in fact the study you refer to should have essentially no effect at all on the baryonic mass estimate because the mass represented by those photons was already in the books, just in a different form.

How about taking a look at the first link again, and focusing specifically on the fact that galaxies are twice as bright as we first ASSUMED and the small stars are 4 times as numerous as we first thought. Why wouldn't those revelations result in ANY modification of your baryonic mass estimates?

Note that in the introduction and in the conclusions section, Driver, et al., 2008 have pointed out the persistent conflict between the assumption of optically thin galaxies (implying that most starlight photons directly escape the galaxy) and the observation of significant far-IR emission (implying that a significant fraction of starlight photons do not directly escape the galaxy but rather indirectly escape as far-IR photons emitted by dust grains heated by starlight). That far-IR emission, which has not been adjusted by Driver, et al., 2008 is the very same emission used to derive star formation rates, and thereby gas masses for galaxies cosmologically. Hence, the effect Mozina is implying, that baryonic mass has been overlooked, is fallacious

The problem for Mozphyzics is that the adjustment can go either way - if stars are bluer than previously thought, this reduces the total star mass.

I'm confused. It sounds like you're saying that the total luminosity of starlight was already known accurately, because it was based on observed far-IR emission from dust. Is that correct?

That baryonic gas has always been included in the mass budget, and offsets the missing stellar mass. The two (gas mass & stellar mass) won't be precisely the same, but it does falsify the notion that there is such a large hole in the baryonic mass budget that needs to be filled.

I hope I did a better job explaining it this time around.

Sounds interesting. Maybe I can help.Tim Thomson said:...We are having this discussion because Mozina thinks that dark matter cannot be anything but ordinary baryonic matter and that the implication to be drawn from Driver, et al., 2008 is that we have overlooked large amounts of baryonic mass by underestimating the number of stars in galaxies...

It certainly does. Science progresses, which means that most people are wrong most of the time. Maybe I'm one of them, but I think there's a problem with the Lambda-CDM model, and that there's a problem with what you're saying too.Ah, but the sword of physics cuts both ways...

There is an exotic form of matter known to man. We've known about it for nearly a hundred years. It's a gravitational field. It's so exotic that it doesn't consist of particles, and you can hardly call it matter. But think about what Einstein said in The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity. He said "the energy of the gravitational field shall act gravitatively in the same way as any other kind of energy". There's energy in a gravitational field, and it has a mass equivalence. It causes gravity. People tend to forget about this, sometimes citing the vacuum catastrophe, but IMHO that's a mistake because it flies in the face of general relativity, a robust well-tested theory.There are no exotic forms of matter known to man. IMO it only makes sense to be "conservative" in terms of "filling in any gaps" in any theory with NORMAL baryonic material, whenever and wherever possible. That "conservatism" is directly related to my preference for KNOWN PHYSICS and KNOWN forms of matter.

I've seen a lot of people fiercely defending dark matter in the form of particles likes WIMPs, so I empathize with your sentiment. But I haven't read much of the thread, so I don't know Tim's stance.Tim's approach seems to be exactly the opposite from my perspective. The "conservatism" is aimed at "protecting the status quo" rather than filling in the gaps of the "dark" parts of his current theory and understanding. It's almost as through he INSISTS that some sort of exotic matter MUST exist. Maybe, and maybe not. We won't know however if we never actually attempt to ELIMINATE the need for exotic types of matter and we constantly favor a "dark matter=exotic matter" approach.

Yes, but flat galactic rotation curves do stand out as being radically different to planetary orbits. Your miscounting of stars has got to be amazingly wrong to account for that.Another thing that this paper demonstrates is that it is unlikely that we even know how to properly count the number of stars in a galaxy, let alone their mass...

In my experience people have something of a tendency to believe in things for which there is no evidence, and to dismiss the evidence that challenges that belief. Religious people certainly do it, but scientists do it too. And so, I'm afraid, so people who consider themselves to be skeptics.This is actually a fascinating discussion IMO, mostly because it shows the difference between a desire to protect a belief system and a desire to tear it apart. The "skeptic" is always unlikely to take the same path as the "true believer", even if both honestly attempt to address the data. I don't question that fact that Tim's method works, I simply don't believe it's the "best" way to explain the data.

Sounds interesting. Maybe I can help.

It certainly does. Science progresses, which means that most people are wrong most of the time. Maybe I'm one of them, but I think there's a problem with the Lambda-CDM model, and that there's a problem with what you're saying too.

There is an exotic form of matter known to man. We've known about it for nearly a hundred years. It's a gravitational field. It's so exotic that it doesn't consist of particles, and you can hardly call it matter. But think about what Einstein said in The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity. He said "the energy of the gravitational field shall act gravitatively in the same way as any other kind of energy". There's energy in a gravitational field, and it has a mass equivalence. It causes gravity. People tend to forget about this, sometimes citing the vacuum catastrophe, but IMHO that's a mistake because it flies in the face of general relativity, a robust well-tested theory.

I've seen a lot of people fiercely defending dark matter in the form of particles likes WIMPs, so I empathize with your sentiment. But I haven't read much of the thread, so I don't know Tim's stance.

Yes, but flat galactic rotation curves do stand out as being radically different to planetary orbits. Your miscounting of stars has got to be amazingly wrong to account for that.

In my experience people have something of a tendency to believe in things for which there is no evidence, and to dismiss the evidence that challenges that belief. Religious people certainly do it, but scientists do it too. And so, I'm afraid, so people who consider themselves to be skeptics.

I hope I did a better job explaining it this time around.

Yes, at least it made it easier for me.

It seems that we already knew the total energy spectrum, and the Driver paper just clarifies where that energy actually comes from.

Drive, et. al., claim there truly is more energy from blue stars. If some of that blue star energy was being shifted to the red, that means we have less actual energy from red stars or protostars.

Unfortunately, the red stars or protostars have lots of mass for a given energy output, and blue stars have lots of energy output for a given mass.

So, more blue stars and fewer red stars and protostars would mean less mass overall, right?

FYI, Wrangler, This paper is not being discussed. It has already been discussed but unfortunately MM has not understood yet what an initial mass function is. It distribiutes a given initial mass of stars into the various populations.FYI, as you're looking for way to increase the brightness, keep in mind that there is a second paper and article that we're discussing that has a bearing on this discussion:

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/features.cfm?feature=2287

http://iopscience.iop.org/0004-637X/695/1/765

Once again, he chooses to link to a news report and avoid the science paper (Evidence for a Nonuniform Initial Mass Function in the Local Universe; Meurer, et al., The Astrophysical Journal 695(1): 765-780, April 2009).

Once again, let us look at the abstract of the paper:

...

But the estimation of mass from total luminosity is not going to be sensitive to this distribution, because the same total mass (and therefore the same total luminosity) can be distributed in many ways over the stellar mass function.

The results also mean that there is about 20 percent more mass in stars than previously thought. But since stars make up such a small percentage of the universe to begin with — dark matter and dark energy account for 95 percent or so — it is a small adjustment over all.

“Basically increasing the stellar mass in the nearby universe by 20 percent has little impact,” Dr. Driver said in an e-mail message from Scotland.

There is an exotic form of matter known to man. We've known about it for nearly a hundred years. It's a gravitational field. It's so exotic that it doesn't consist of particles, and you can hardly call it matter. But think about what Einstein said in The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity. He said "the energy of the gravitational field shall act gravitatively in the same way as any other kind of energy". There's energy in a gravitational field, and it has a mass equivalence. It causes gravity.

People tend to forget about this, sometimes citing the vacuum catastrophe, but IMHO that's a mistake because it flies in the face of general relativity, a robust well-tested theory.

FYI, Wrangler, This paper is not being discussed.

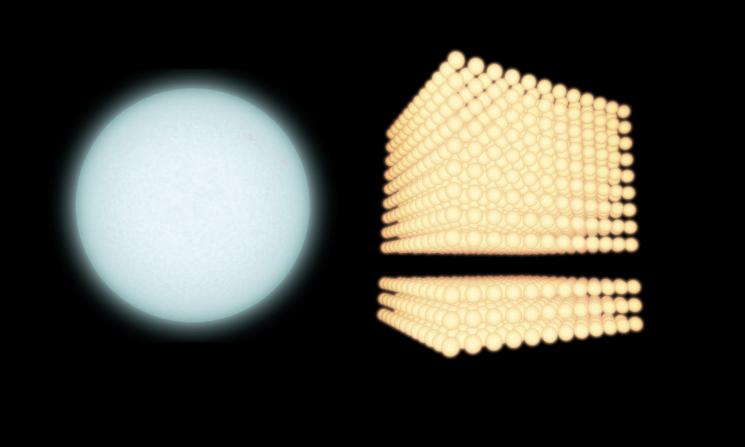

This diagram illustrates the extent to which astronomers have been underestimating the proportion of small to big stars in certain galaxies. Data from NASA's Galaxy Evolution Explorer spacecraft and the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile have shown that, in some cases, there can be as many as four times more small stars compared to large ones.

In the diagram, a massive blue star is shown next to a stack of lighter, yellow stars. These big blue stars are three to 20 times more massive than our sun, while the smaller stars are typically about the same mass as the sun or smaller. Before the Galaxy Evolution Explorer study, astronomers assumed there were 500 small stars for every massive one (lower stack on right). The new observations reveal that, in certain galaxies, this estimation is off by a factor of four; for every massive star, there could be as many as 2,000 small counterparts (entire stack on right).

Ohhh - pretty picture MM!What RC means is that he doesn't want to discuss the fact that we have evidence that we not only underestimate the LARGEST stars in the galaxies, we grossly underestimate the number of smaller stars as well. He doesn't like to discuss that.

...snipped another MM "I see bunnies in the clouds" image...

! And all you can find is a paper that increases their mass by a factor of 1.2. You do see the enormous problem there?

! And all you can find is a paper that increases their mass by a factor of 1.2. You do see the enormous problem there? !

!You need to read Adding up Stars in a Galaxy again and note that it is about the proportion of stars, not the total mass of the stars.

It may be the Evidence for a Nonuniform Initial Mass Function in the Local Universe paper by Gerhardt R. Meurer, et al. who use the GALEX observations and one author is from the Cerro observatory.Can anyone point me to the paper that drove this press release? I am having trouble finding it.

Are they assuming a constant overall energy output while changing the star proportion?

I want to do some of my own calculations of mass sensitivity.

Not actually.That baryonic gas has always been included in the mass budget, and offsets the missing stellar mass. The two (gas mass & stellar mass) won't be precisely the same, but it does falsify the notion that there is such a large hole in the baryonic mass budget that needs to be filled.

I hope I did a better job explaining it this time around.I'm not even discussing the gas/dust yet, and I assumed that you already accurately accounted for it's mass. Nobody was arguing that point, at least not yet.

Ya, including ordinary matter. I've yet to hear you folks address that "dust" in space revelation from a few years ago, or that revelation that galaxies are twice as bright as first thought, or that "stellar recount" data that that shows that small stars were underestimated by a factor of FOUR! About all I see are papers claiming "SUSY did this in the sky, SUSY did that in the sky". SUSY seems to be dead. What justification do you even have for exotic forms of matter at this point?There's a fair number of candidates for a dark matter particle.

{ ... }

IMO it is your fault for failing to consider the fact that your ordinary mass estimated were probably (now known to be) botched to begin with, and no real steps have ever been taken to MINIMIZE the need for exotic types of mass.

How about that dust problem? What about that stellar recount problem? Don't you think it would make sense in light of recent laboratory analysis to go back and revisit your ORDINARY mass estimates with the express intent of minimizing or doing away with exotic brands of matter?

Sorry sol, on this point I simply have to absolutely, positively, without any doubt, disagree with your assessment. Here's why:Fact: Dark matter is almost certainly not baryonic, because all baryonic possibilities have been ruled out by direct searches and/or by various other effects it would have produced.

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/17/science/space/17univ.html

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/features.cfm?feature=2287

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2009/06/090609-most-massive-black-holes.html

There is clear evidence IMO that not only were the original mass estimates WRONG they were wrong by a lot. In over three years I haven't seen your industry budge one single percentage point from their emotional need for "exotic" brands of matter. In fact I've seen no movement AT ALL! That says to me that your industry just isn't interested in admitting their mistakes in their mass estimation techniques.

Spare me the lecture about the Black hole not helping find the missing mass, yada, yada, yada. I'm just noting that the industry hasn't budged a single percentage point in 3 years. That alone says volumes IMO.