You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

I don't think space is expanding.

- Thread starter Mike Helland

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Mike Helland

Philosopher

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2020

- Messages

- 5,244

The contradiction has nothing to do with the refractive index of empty space. It's a consequence of simple relative velocities. Two photons from the same direction but different distances, arriving at the same place at the same time (e.g. the telescope aperture), will arrive at different angles relative to the instrument if (1) they're traveling at different speeds as your theory claims would occur, and (2) the target is moving laterally to the direction of travel of the photons, as the Hubble usually is.

The instrument can be tilted to compensate for this effect, but that only works consistently if all the incident light has the same velocity.

Ok, so if light from a galaxy is propagating in all directions, and we're moving laterally to it:

https://openmedia.gallery/view/1788

So... if we want to look at that red galaxy, we view at one angle on the left, which we adjust as we move to the right... why would the speed of the light affect which direction we look to see the galaxy?

Whether photons are traveling at c or 0.3c, the galaxy is still in the same direction, is it not?

Mike Helland

Philosopher

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2020

- Messages

- 5,244

Light doesn't get "trapped" at the Hubble limit, any more than ships drop off the edge of the Earth at the horizon.

Light moving at c through space expanding faster than c.

What do you suppose is in store for the photon? An eternity of ever increasing void?

RecoveringYuppy

Penultimate Amazing

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2006

- Messages

- 14,185

Light moving at c through space expanding faster than c.

What do you suppose is in store for the photon? An eternity of ever increasing void?

Are you faster than you are tall?

Mike Helland

Philosopher

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2020

- Messages

- 5,244

Are you faster than you are tall?

Once the photon reaches space that expands faster than c, anything in front of it will be forever unreachable.

This is slightly modified when the expansion rate is changing over time.

RecoveringYuppy

Penultimate Amazing

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2006

- Messages

- 14,185

Please just tell me if you are faster than you are tall.

Ziggurat

Penultimate Amazing

- Joined

- Jun 19, 2003

- Messages

- 61,867

Yeah, good point.

"both v and D are reference-frame dependent, and as you change reference frames, they change in incompatible ways. If your equation holds in one reference frame, it will not hold in any other reference frame."

Can you give an example of that?

Let's use units such that H = 1 and c = 1, for simplicity, so that v = 1 - D.

Reference frame 1: stationary star emits light at t=0, x=0. At D = 0.5, v = 0.5. When does that happen?

v = dx/dt = 1 - x

dx/(1-x) = dt

Integrate both sides:

t = -ln(1-x) = -ln(0.5) = ln(2) = 0.69.

So x = 0.5, t = 0.69 is where v = 0.5.

OK, now let's switch reference frames. We'll keep a common origin, but our reference frame is traveling at 0.25c in the positive direction relative to the original reference frame. We can do the same calculations in this frame, and we will find that x' = 0.5, t' = 0.69, and v' = 0.5.

But x'=0.5 and t' = 0.69 is farther away from the origin, in the unprimed frame, than x=0.5 and t=0.69, and v'=0.5 equates to v>0.5. So the primed observer will say that the light is going farther before it slows down than the unprimed observer. They will disagree with each other, once you take their reference frame differences into account. And here's the kicker: that applies whether we use Newtonian coordinate transformations OR relativistic transformations to switch between the primed and unprimed frames.

Is there any possible set of coordinate transformations which will get you from one set of coordinates to the other? I don't think there are, but maybe I'm wrong on that count. What I do know is that no set of coordinate transformations will both allow them to agree AND match up with the various experiments used to confirm the accuracy of special relativity.

Mike Helland

Philosopher

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2020

- Messages

- 5,244

Please just tell me if you are faster than you are tall.

That's nonsense.

And if you think trapped photons in expanding space is nonsense, I totally agree.

Since we are at the Hubble limit of other Hubble volumes, there's trapped photons all around us.

I made a video, if you want to make fun of that:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AsmhhYCh4N8

RecoveringYuppy

Penultimate Amazing

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2006

- Messages

- 14,185

Why?That's nonsense.

Mike Helland

Philosopher

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2020

- Messages

- 5,244

Why?

"For objects at the Hubble limit the space between us and the object of interest has an average expansion speed of c. So, in a universe with constant Hubble parameter, light emitted at the present time by objects outside the Hubble limit would never be seen by an observer on Earth. "

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hubble_volume

Mike Helland

Philosopher

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2020

- Messages

- 5,244

Let's use units such that H = 1 and c = 1, for simplicity, so that v = 1 - D.

Reference frame 1: stationary star emits light at t=0, x=0. At D = 0.5, v = 0.5. When does that happen?

v = dx/dt = 1 - x

dx/(1-x) = dt

Integrate both sides:

t = -ln(1-x) = -ln(0.5) = ln(2) = 0.69.

So x = 0.5, t = 0.69 is where v = 0.5.

OK, now let's switch reference frames. We'll keep a common origin, but our reference frame is traveling at 0.25c in the positive direction relative to the original reference frame. We can do the same calculations in this frame, and we will find that x' = 0.5, t' = 0.69, and v' = 0.5.

But x'=0.5 and t' = 0.69 is farther away from the origin, in the unprimed frame, than x=0.5 and t=0.69, and v'=0.5 equates to v>0.5. So the primed observer will say that the light is going farther before it slows down than the unprimed observer. They will disagree with each other, once you take their reference frame differences into account. And here's the kicker: that applies whether we use Newtonian coordinate transformations OR relativistic transformations to switch between the primed and unprimed frames.

Is there any possible set of coordinate transformations which will get you from one set of coordinates to the other? I don't think there are, but maybe I'm wrong on that count. What I do know is that no set of coordinate transformations will both allow them to agree AND match up with the various experiments used to confirm the accuracy of special relativity.

Thank you very much.

You've been very helpful.

In the expanding models I was making, it was pretty obvious right away that putting the target in motion or putting the light source in motion makes a difference, indicating a preferred frame.

My solution was to not compare the photon's x position, but the photon's distance from the source's x position. If the source was in motion, then, the photon's motion would be linked to it.

Which is basically a kind of emitter theory. But the model's worked regardless of whether the source was in a rest or not.

Which we both know is externally inconsistent, as you say "AND match up with the various experiments used to confirm the accuracy of special relativity."

But you were saying the theory isn't internally consistent. And I actually did work that out.

It's just bad news for external consistency to relativity.

Agreed?

RecoveringYuppy

Penultimate Amazing

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2006

- Messages

- 14,185

Why are you evading my question? Do you have something to hide about whether you're faster or taller?"For objects at the Hubble limit ... blah blah blah

Mike Helland

Philosopher

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2020

- Messages

- 5,244

Why are you evading my question? Do you have something to hide about whether you're faster or taller?

You're not be straightforward, and you're talking nonsense.

My change in position over time is difficult to relate to my height.

And you know that.

But velocity is km/s, and the velocity of a photon, and the velocity of a distance galaxy are relatable. And Hubble's constant is (km/s) / distance so you just multiply it by a distance and you get km/s.

Do you deny there's a Hubble limit in the standard model where photon encounter space expanding faster than they can travel?

RecoveringYuppy

Penultimate Amazing

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2006

- Messages

- 14,185

So when does a photon reach space that is expanding faster than c???But velocity is km/s, and the velocity of a photon, and the velocity of a distance galaxy are relatable. And Hubble's constant is (km/s) / distance so you just multiply it by a distance and you get km/s.

Mike Helland

Philosopher

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2020

- Messages

- 5,244

So when does a photon reach space that is expanding faster than c???

Hubble's Law:

V = H * D

Hubble's Limit is:

H * D = c

Therefore, the distance is

D = c / H

That works out 13-14 billion light years depending on the value of H.

Mike Helland

Philosopher

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2020

- Messages

- 5,244

Ten billion years from now, assume the same expansion rate as today, the age of the universe in the standard model would be 24 billion years, and Hubble's Limit would be 14 billion light years.

We live, apparently by pure coincidence, when Hubble's Limit and the age of the universe are basically the same.

That's not very Copernican.

We live, apparently by pure coincidence, when Hubble's Limit and the age of the universe are basically the same.

That's not very Copernican.

Ok, so if light from a galaxy is propagating in all directions, and we're moving laterally to it:

https://openmedia.gallery/view/1788

So... if we want to look at that red galaxy, we view at one angle on the left, which we adjust as we move to the right... why would the speed of the light affect which direction we look to see the galaxy?

Whether photons are traveling at c or 0.3c, the galaxy is still in the same direction, is it not?

That diagram doesn't show the issue. The distance to the galaxy is much larger than your diagram shows, so all the photons from the galaxy are parallel. (There is no measurable parallax, in other words, even if you observe from opposite edges of the solar system.) So no, you don't adjust left and right as you move in one direction "past" the object. It's not a parallax issue.

Suppose you want to study the light from one particular distant galaxy, whose apparent width from the solar system is one arcsecond. We don't want to use any lenses or mirrors, because (you've argued) those can change the properties of the light we want to measure. So instead, we aim a long narrow tube directly at the galaxy, with our measuring device at the near end ("bottom") of the tube. By "aim" I mean that the tube is perfectly parallel to the direction the photons from that galaxy are moving through the solar system. The tube is black on the inside. Any photons from other directions outside the expected one-arcsecond field, even if they happen to enter the tube, will be absorbed by the inner wall of the tube and won't reach the sensor.

Let's say we make the inner bore of our tube one inch in diameter. To have a field of view of one arcsecond, the tube must then be about three and a quarter miles (17,000 feet) long.

Once a photon enters the tube, if it's traveling at c, it takes 17 microseconds to reach the sensor.

That's not a problem, as long as the tube is not moving laterally, perpendicularly to its length and to the direction the photons are traveling. But what if it does start moving in that manner, let's say left to right on your diagram, at a speed of, let's say, 7.6 km/sec.

Now imagine a photon from the distant galaxy enters the open end of the tube. It will reach the detector in 17 microseconds. But the tube moves its own width sideways every 3.3 microseconds. So long before any photon from the galaxy can reach the sensor, the left inner wall of the tube reaches it, and absorbs it.

What can we do about that? We can tilt the tube a little to the right (clockwise, in your diagram) so that, as each photon from the distant galaxy travels down the tube, the tilt counteracts the lateral movement of the tube, so that the moving photon stays the same distance from the walls of the moving tube. The angle we must tilt the tube is the arc tangent of the ratio of the tube's lateral velocity and c. That's about 5.2 arcseconds.

After the tilt (aka correction for aberration), the sensor at the bottom of the moving tube will again be detecting photons from the distant galaxy.

Several critical points here:

1. After the tilt, the tube will no longer be parallel to the direction those photons are moving. It will no longer be aimed precisely at the apparent position of the distant galaxy.

2. At that lateral speed, the amount of tilt required is significantly greater than the field of view of the tube itself.

3. That lateral speed in this example happens to be the orbital speed of the Hubble telescope. This will be important later.

4. That amount of tilt will only work for light that's traveling at c. If the light were traveling at 0.5c, for instance, it would still hit the wall of the tube by halfway down, and would need twice as much tilt (10.4 arcseconds) to be able to reach the sensor.

But twice the tilt wouldn't work for light that was traveling at c, or at, say, 0.8c. That light could only make it part way down the tube before hitting the right wall. A given angle aberration correction only works for a specific speed (or a rather narrow speed range, at best) of photons.

And this will be important later: the longer and/or narrower the tube, the more constrained the speed range of photons will make it to the sensor.

Okay, so what if instead of moving laterally in a constant velocity, the tube were in orbit around the Earth? Note that regardless of the direction of the target it's aimed at, it cannot orbit the Earth without moving laterally to that direction most of the time. Not always at the maximum lateral velocity of 7.6km per second, but more often than not at greater than half that speed. And that relative lateral motion is reversing direction every half orbit.

So the tilt, the aberration correction, must be constantly changing to keep the target in the tube's field of view. This is not to keep the tube "aimed at" the target; quite the contrary! It's to tilt the tube this way and that as needed so that photons from the target that enter the tube don't hit the walls of the tube as those walls orbit at 7.6km/sec in different relative directions. (If the orbit were a perfect circle, and there weren't also other motions like the earth's around the sun to compensate for, the tilting motion would trace out an ellipse with each orbit).

But the fact remains that this ongoing correction only works if the light from the target is moving at (or very close to) the velocity the mission planners expected it to be.

That tube represents one pixel of the Hubble's image. With two differences:

1. To accurately represent the Hubble's angular resolution, the tube should be at least ten times longer.

2. For the Hubble, if the aberration correction is wrong, light from a given pixel's target square tenth-of-an-arcsecond doesn't hit a wall of a tube and get absorbed. Instead, it lands on some other pixel nearby. Some other pixel that's supposed to be imaging a different square-tenth-of-an-arcsecond piece of sky. In other words, the image blurs.

But if the speed of the light from objects at different cosmic distances within the same Hubble image is different, then the aberration correction cannot be right for all the objects imaged at the same time. Different photon speeds need different angles of correction. All long-exposure images of the deep field would show most of the deep field objects blurred.

That's why the Hubble deep field images completely falsify your conjecture.

Reformed Offlian

Master Poster

Hubble's Law:

V = H * D

Hubble's Limit is:

H * D = c

Therefore, the distance is

D = c / H

That works out 13-14 billion light years depending on the value of H.

The Hubble limit is not a place that a photon ever reaches; it is a distance from a given observer at a given time. There's no inertial frame in the universe where photons don't whizz past the observer at c.

Now, it is possible for the universe to have expanded to the point where a photon leaves one galactic cluster and finds that the next nearest cluster is receding faster than it can reach it, but that's not the same as being "trapped." Bored and lonely, perhaps, but not trapped.

Last edited:

Mike Helland

Philosopher

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2020

- Messages

- 5,244

Except that a photon never arrives at a place that says: "Here is the Hubble limit". If it travels 14 billion years, it will simply find itself in the middle of a normal-seeming bit of local space with a universe expanding around it much like it was at its starting point. It doesn't get trapped.

Now, there may come a point at which it leaves one galactic cluster and finds that the next nearest cluster is receding faster than it can reach it, but that's not the same as being "trapped." Bored and lonely, perhaps, but not "trapped."

Let's say you're running the 50 yard dash.

You run at 5 mph. The finish line is moving away from you at 6 mph.

How long until you reach the finish line?

That, according to the standard model, is going on at every where in space.

Call it trapped, call it bored and lonely.

It's social distance game is on point.

Mike Helland

Philosopher

- Joined

- Nov 29, 2020

- Messages

- 5,244

That diagram doesn't show the issue. The distance to the galaxy is much larger than your diagram shows, so all the photons from the galaxy are parallel. (There is no measurable parallax, in other words, even if you observe from opposite edges of the solar system.) So no, you don't adjust left and right as you move in one direction "past" the object. It's not a parallax issue.

Suppose you want to study the light from one particular distant galaxy, whose apparent width from the solar system is one arcsecond. We don't want to use any lenses or mirrors, because (you've argued) those can change the properties of the light we want to measure. So instead, we aim a long narrow tube directly at the galaxy, with our measuring device at the near end ("bottom") of the tube. By "aim" I mean that the tube is perfectly parallel to the direction the photons from that galaxy are moving through the solar system. The tube is black on the inside. Any photons from other directions outside the expected one-arcsecond field, even if they happen to enter the tube, will be absorbed by the inner wall of the tube and won't reach the sensor.

Let's say we make the inner bore of our tube one inch in diameter. To have a field of view of one arcsecond, the tube must then be about three and a quarter miles (17,000 feet) long.

Once a photon enters the tube, if it's traveling at c, it takes 17 microseconds to reach the sensor.

That's not a problem, as long as the tube is not moving laterally, perpendicularly to its length and to the direction the photons are traveling. But what if it does start moving in that manner, let's say left to right on your diagram, at a speed of, let's say, 7.6 km/sec.

Now imagine a photon from the distant galaxy enters the open end of the tube. It will reach the detector in 17 microseconds. But the tube moves its own width sideways every 3.3 microseconds. So long before any photon from the galaxy can reach the sensor, the left inner wall of the tube reaches it, and absorbs it.

What can we do about that? We can tilt the tube a little to the right (clockwise, in your diagram) so that, as each photon from the distant galaxy travels down the tube, the tilt counteracts the lateral movement of the tube, so that the moving photon stays the same distance from the walls of the moving tube. The angle we must tilt the tube is the arc tangent of the ratio of the tube's lateral velocity and c. That's about 5.2 arcseconds.

After the tilt (aka correction for aberration), the sensor at the bottom of the moving tube will again be detecting photons from the distant galaxy.

Several critical points here:

1. After the tilt, the tube will no longer be parallel to the direction those photons are moving. It will no longer be aimed precisely at the apparent position of the distant galaxy.

2. At that lateral speed, the amount of tilt required is significantly greater than the field of view of the tube itself.

3. That lateral speed in this example happens to be the orbital speed of the Hubble telescope. This will be important later.

4. That amount of tilt will only work for light that's traveling at c. If the light were traveling at 0.5c, for instance, it would still hit the wall of the tube by halfway down, and would need twice as much tilt (10.4 arcseconds) to be able to reach the sensor.

But twice the tilt wouldn't work for light that was traveling at c, or at, say, 0.8c. That light could only make it part way down the tube before hitting the right wall. A given angle aberration correction only works for a specific speed (or a rather narrow speed range, at best) of photons.

And this will be important later: the longer and/or narrower the tube, the more constrained the speed range of photons will make it to the sensor.

Okay, so what if instead of moving laterally in a constant velocity, the tube were in orbit around the Earth? Note that regardless of the direction of the target it's aimed at, it cannot orbit the Earth without moving laterally to that direction most of the time. Not always at the maximum lateral velocity of 7.6km per second, but more often than not at greater than half that speed. And that relative lateral motion is reversing direction every half orbit.

So the tilt, the aberration correction, must be constantly changing to keep the target in the tube's field of view. This is not to keep the tube "aimed at" the target; quite the contrary! It's to tilt the tube this way and that as needed so that photons from the target that enter the tube don't hit the walls of the tube as those walls orbit at 7.6km/sec in different relative directions. (If the orbit were a perfect circle, and there weren't also other motions like the earth's around the sun to compensate for, the tilting motion would trace out an ellipse with each orbit).

But the fact remains that this ongoing correction only works if the light from the target is moving at (or very close to) the velocity the mission planners expected it to be.

That tube represents one pixel of the Hubble's image. With two differences:

1. To accurately represent the Hubble's angular resolution, the tube should be at least ten times longer.

2. For the Hubble, if the aberration correction is wrong, light from a given pixel's target square tenth-of-an-arcsecond doesn't hit a wall of a tube and get absorbed. Instead, it lands on some other pixel nearby. Some other pixel that's supposed to be imaging a different square-tenth-of-an-arcsecond piece of sky. In other words, the image blurs.

But if the speed of the light from objects at different cosmic distances within the same Hubble image is different, then the aberration correction cannot be right for all the objects imaged at the same time. Different photon speeds need different angles of correction. All long-exposure images of the deep field would show most of the deep field objects blurred.

That's why the Hubble deep field images completely falsify your conjecture.

Thank you very much for taking the time to spell this out very clearly.

It was pretty exciting to read. I wonder if you've seen the experiment for the hypothesis I propose that involves a space tube.

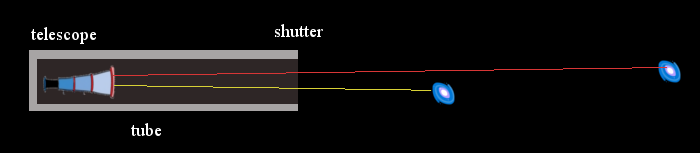

The idea here is if high z light is traveling slower than c, shuttering the tube should eliminate light from entering, leaving what's in there to travel to the sensor. A high speed camera, if the hypothesis is right, would reveal the final frames only contain the oldest light.

I'm all about space tube.

I was thinking about shuttering the tube, but you're talking about our motion naturally shuttering slow light leaving new light.

The z would have to be pretty high for Earth's motion to be a factor.

If the galaxies are actually much closer than we think, slow moving light would make it look much farther away, and we take care of the angle's based on an overestimation of distance (which is showed in comparison of simulations).

But that's besides the amazing post you just made.

I'm just curious, the tube in your post is a pixel? Not literally a tube?

Doesn't the light entering the Hubble's sensors bounce off a big mirror first?

- Status

- Not open for further replies.