Would that count as perjury? Can a prosecutor get in trouble for false statements?

As in all such questions of law, it depends.

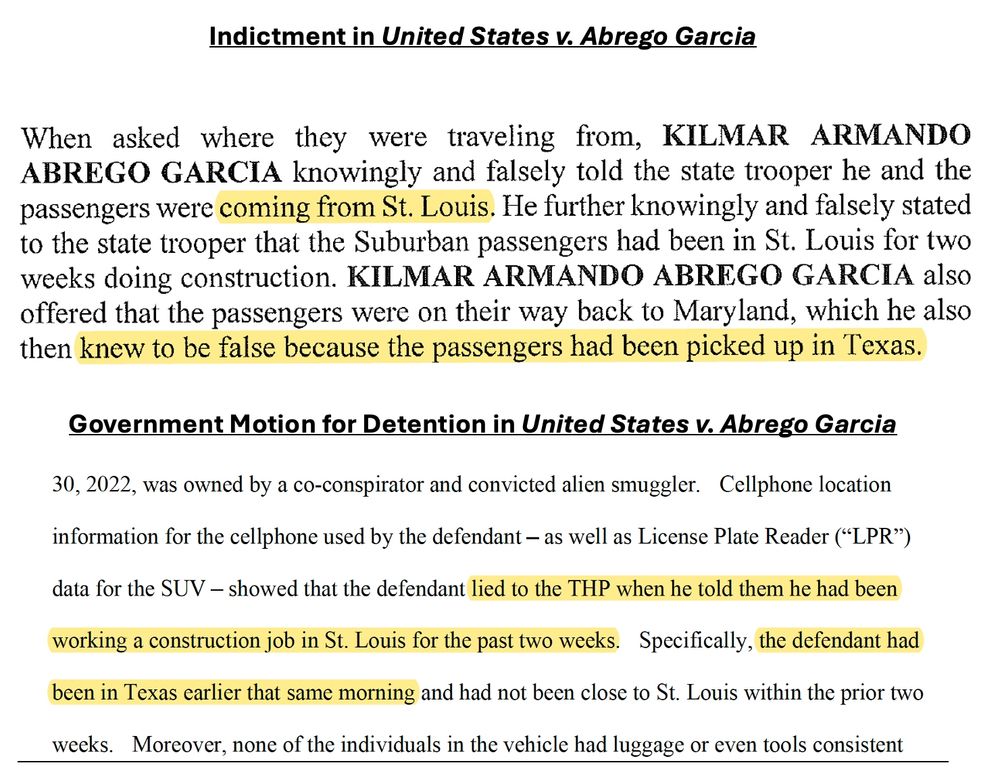

An indictment is by a grand jury, but the language of the indictment is drafted by the prosecutor. The grand jury endorses the language of the indictment after the prosecutor presents evidence in favor of each factual claim. There is no judicial rule requiring a prosecutor to present exculpatory evidence to a grand jury, although it was Dept. of Justice policy to do so. The grand jury indictment provides the basis for a criminal complaint to which the U.S. attorney must swear. That is, just because a grand jury indicts you doesn't mean a federal prosecutor will file charges. Thus ultimately the U.S. attorney is primarily responsible for the integrity of the claim for Rule 11 purposes.

A referral for criminal prosecution is an allegation of fact made by the referrer. The referral may be sworn or unsworn. It is ultimately the job of the prosecutor to conduct its own sufficient investigation before bringing an indictment bill before a grand jury. Thus one way this can be resolved is if the Tennessee-based U.S. attorney found its own evidence that contradicted the Dept. of Homeland Security referral. It's not clear at this stage whether that happened, because the charge here is a 7-page summary, not the dozens of pages of speaking indictments that were more common before the Bondi era.

A prosecutor who brings charges that she knows are contravened by facts takes one step toward prosecutorial misconduct. But a prosecutor is allowed to apply judgment at the complaint stage regarding which facts are more credible than others. And for obvious reasons, a prosecutor might want to emphasize the side of the story that suggests guilt. However, in the discovery stage the exculpatory evidence must be provided to the defense, otherwise a

Brady violation occurs and the judge has the option to dismiss a charge that was predicated on a

Brady violation.

The defense has the opportunity to challenge the providence of the complaint in the preliminary hearing. In that case, the defense can question the prosecution about the discrepancy between the DOHS referral and the indictment. The prosecution would be obliged to state what evidence it presented to the grand jury to convince them that the defendant lied as charged in the indictment. However at that stage the result could be a superseding indictment in which that particular factual claim is removed. The prosecutor would not be sanctioned.

In a civil claim under

Bivens, the judgment of the prosecutor then becomes much more important. The prosecutor would have a heightened responsibility to defend the charges as properly supported in light of the available facts. In addition, AG Bondi's public remarks in which she accused Abrego Garcia of criminal activity not charged in the indictment—and other prejudicial comments—would tend to argue in favor of malicious prosecution.