Belz...

Fiend God

No you didn't.

You're really taking denialism to new heights.

No you didn't.

No: the only complication is the question of whether you are willing to try to understand the answers to your questions.Lets go back and see what passed for conversation, before I asked the questions....

But now, it's a lot more comilicated than that.

Tamino takes on the Pause :

Global Temperature: the Post-1998 Surprise

http://tamino.wordpress.com/2014/01/30/global-temperature-the-post-1998-surprise/

Suffice to say the Pause does not come out of the encounter well.

If the Wikipedia article stated the facts up front, it probably would have been!that could have and should been concluded in about 5 minutes

It does not say the other part in the definition! It does appear further down.The greenhouse effect is a process by which thermal radiation from a planetary surface is absorbed by atmospheric greenhouse gases, and is re-radiated in all directions. Since part of this re-radiation is back towards the surface and the lower atmosphere, it results in an elevation of the average surface temperature above what it would be in the absence of the gases.[1][2]

So there it is, and if anyone had just quoted like I did, the first question is answered!. (but not the second)Each layer of atmosphere with greenhouses gases absorbs some of the heat being radiated upwards from lower layers. It re-radiates in all directions, both upwards and downwards; in equilibrium (by definition) the same amount as it has absorbed. This results in more warmth below. Increasing the concentration of the gases increases the amount of absorption and re-radiation, and thereby further warms the layers and ultimately the surface below.[8]

Greenhouse gases—including most diatomic gases with two different atoms (such as carbon monoxide, CO) and all gases with three or more atoms—are able to absorb and emit infrared radiation. Though more than 99% of the dry atmosphere is IR transparent (because the main constituents—N2, O2, and Ar—are not able to directly absorb or emit infrared radiation), intermolecular collisions cause the energy absorbed and emitted by the greenhouse gases to be shared with the other, non-IR-active, gases.

I would say that nailed it. In other words, the answer should have been "CO2 molecules increase their energy by absorbing IR, then they either impart that energy to other non-greenhouse gas molecules by intermolecular collisions, or re-radiate the same energy in all directions.Reality Check said:Yes, yes and yes (but really needs a duhDoes a CO2 molecule that has warmed, by absorbing IR, impart that energy to other non-greenhouse gas molecules in the form of translational kinetic energy, or does it make the atmosphere warmer only in the sense of re-radiating IR?

Is there a difference between the two?!), r-j.

Molecules in the atmosphere collide with other molecules in the atmosphere. ETA: So a CO2 molecule that has increased its "translational kinetic energy" can transfer that energy to any other molecule that it collides with.

Molecules that absorb light (and so gain energy or as you rather badly put it "warm"), emit light.

Collision is not emission.

CO2 doesn't trap anything, it either transfers the energy to N2, or re-radiates the IR in all directions. Neither action lasts long enough for the CO2 to have "trapped" the IR energy.C02 MAINTAINS a warmer atmosphere than would be present without it. CO2 alters the radiative balance by trapping outgoing IR

Not according to what we have learned. It either changes the direction the IR travels, or heats up N2 molecules. It is only trapped if something takes up the IR and does no re-radiate it again. Like the oceans do.It traps radiation from being reradiated out to space and so keeps the atmosphere habitable.

Prett poorly it would seem, and yet here we are.If you can't ask the questions correctly how can anyone communicate with you.

again, if you had simply quoted the information, we would have moved on. (that was joke)In the pursuit of trying to educate you: Greenhouse effect (the physics of how CO2 in the atmosphere warms the surface of the earth!)

That doesn't make any sense.The molecule has not warmed (There are no changes in latent heat in a higher scale, so to speak)

It does not "impart" any aditional energy in the form of translational kinetic energy as a consequence of that absorption (nothing of consequences).

Like, duh! That was never the question!It does not make the gases in the atmosphere warmer per se by re-radiating IR as those gases are mostly transparent to those IR..

Again, that made no sense. But now it brings up another question. Do CO2 molecules transfer energy to each other by intermolecular collisions? And if so, does that mean the CO2 molecule that just gained energy can radiate it away as IR?It can affect other scattered CO2 molecules by chance in the same way.

If the Wikipedia article stated the facts up front, it probably would have been! It does not say the other part in the definition! It does appear further down.

If it's all understood, then it should be easy to explain how it happens.

A CO2 molecule can lose this energy either by collision with another molecule or by emitting a photon in a random direction. In the lower atmosphere where there are more molecules the former is more likely, in the upper atmosphere the latter is more likely.

So there it is, and if anyone had just quoted like I did, the first question is answered!

Neither action lasts long enough for the CO2 to have "trapped" the IR energy. Not according to what we have learned.

So, if a CO2 molecule transfers the energy of the IF it just absorbed, to a N2 molecule, does the N2 molecule stay more energetic? Or would the N2 lose this energy by collision with another molecule? If the N2 can't absorb the IF, does that mean it can't radiate the energy away? It can only lose this energy by collision with another molecule?

How would the energy return to space?

Does this mean that if there were no greenhouse gases in the air at all, the N2 couldn't lose the energy?

CO2 doesn't trap anything, it either transfers the energy to N2, or re-radiates the IR in all directions. Neither action lasts long enough for the CO2 to have "trapped" the IR energy.

The question is more like, "Since the two mechanism are completely different, what are the different effects of each transfer of energy?".

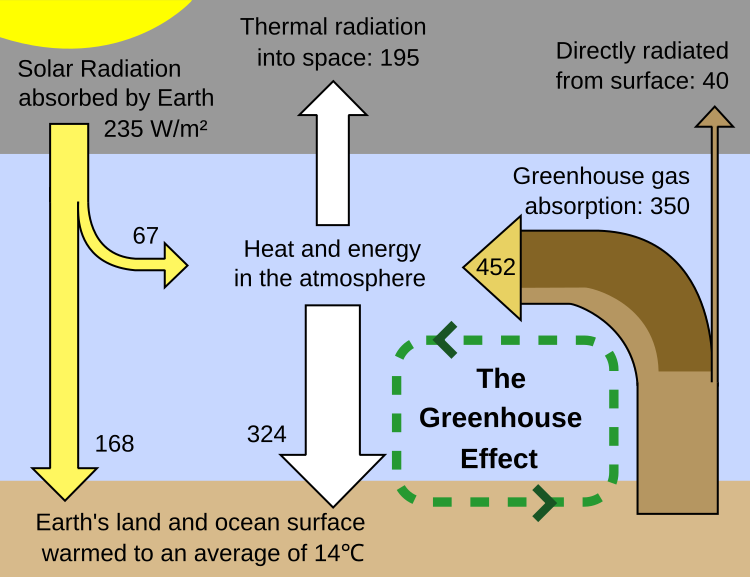

for example, many of the charts that show the energy balance do not list the amount of energy that goes into heating the atmosphere from CO2 from intermolecular collisions. They show all the energy as re-radiating.

Like the Wikipedia one for the greenhouse effect.

[qimg]https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/58/Greenhouse_Effect.svg/750px-Greenhouse_Effect.svg.png[/qimg]

Where does that show "the intermolecular collisions cause the energy absorbed and emitted by the greenhouse gases to be shared with the other, non-IR-active, gases"? And what are the numbers?

Why does any of this matter? Obviously if CO2 is causing N2 to become more energetic (warmer), or in layman's terms, the CO2 warms the air, that is far different than all the IR being re-radiated, either towards the surface or away into space.

Thanks for that. Does that answer the question about the amount of energy that CO2 loses to heat the N2 around it? What about the issue of N2 not being able to radiate away energy?The energy absorbed by CO2 molecules is entirely due to changes in the bonds (vibrational, torsional and tensional) - these produce signature responses that are mapped out with the data held in the HITRANS database. The changes in the bonds affect the molecules momentum and this can be transferredby intermolecular transmission. But CO2 molecules have an indentical chance of being hit by the faster O2 and N2 molecules, effectively the translational energy interactions are balanced. CO2 re-radiating photons in random directions is the dominant transaction for radiating energy.

So, if a CO2 molecule transfers the energy of the IF it just absorbed, to a N2 molecule, does the N2 molecule stay more energetic? Or would the N2 lose this energy by collision with another molecule? If the N2 can't absorb the IF, does that mean it can't radiate the energy away? It can only lose this energy by collision with another molecule?

Does this mean that if there were no greenhouse gases in the air at all, the N2 couldn't lose the energy? How would the energy return to space?

N2 can release energy, by inter-molecular collisions with GHGs that then radiate IR photons and also, as mentioned earlier via UV emission, though that would require multiple GHG collisions adding energy. I don't know the steps required to achieve that and what the energy balance is though.... What about the issue of N2 not being able to radiate away energy? ...

If there was an atmosphere of just N2, no greenhouse gases of any kind, then sunlight wouldn't warm the air at all? And, what warming occurred from the warm surface contacting the N2 atmosphere, that energy couldn't be lost to space? But that is diverging completely from the topic of global warming.

...

I still don't have an answer for how much, if at all, CO2 warms the troposphere. Or the stratosphere. That's the number that doesn't appear on those energy balance charts.

Tropospheric warming and stratospheric cooling have been predicted and measured and are in line with theory.

One reason I brought up the subject. If increasing CO2 only warms by causing the surface to warm, not the atmosphere, then what we expect to see is different than if CO2 warms the N2 of the air. Somebody must know the exact answers to this, because they would have to put that info and numbers into the models.

Except I'm still not sure the answer is correct. If CO2 transfers heat by collisions with O2 and N2 molecules, there is no way it can be re-radiating back the amount of IR the diagrams show.

It's not physically possible.

Because they list the numbers on the diagrams. How could you not know that?How do you know how much is re-radiating back?

Oh I see, a joke. Very funny.By judging the size of the arrows?

Cyclones hitting Australia plummet to 1500-year low

18:00 29 January 2014 by Michael Slezak

Off the chart: cyclone activity in Australia has been lower over the last 40 years than at any time in the past 1500 years. But the seemingly good news comes with a sting in the tail for people living on the coast.

Radar and satellite records of tropical cyclones – rotating storm systems – stretch back only about four decades. For an idea of trends on the longer term, researchers must go underground.

Compared with typical monsoonal rains, the severe rains associated with tropical cyclones are unusually low in the heavier oxygen isotope – oxygen-18. Stalagmites forming in caves record this difference, so by analysing their growth bands – which form each year in the wet season – geologists can establish whether or not a given year was characterised by cyclone activity.

http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn24962-cyclones-hitting-australia-plummet-to-1500year-low.htmlIf cyclones are to become less frequent but more intense, that is bad news for people living on Australia's coast. It suggests they may have to deal with stronger cyclone-induced storm surges and flooding in future. "We've grossly underestimated the risks with building close to sea level," says Nott.

Because they list the numbers on the diagrams. How could you not know that? Oh I see, a joke. Very funny.