edd

Master Poster

- Joined

- Nov 28, 2007

- Messages

- 2,120

http://arxiv.org/abs/1103.5331 - a review with a sensibly restrained attitude I think?

Thanks. Sorry to have been absent for a week, I've been run off my feet.I'm intrigued already.That's a great start!

True. It's kind of out-of-the-box exotic, but simple and obvious when you think about it.I guess that depends on how we define the term "exotic" I suppose.

Yes, gravitons are hypothesized, but taking the lead from QED, they would be virtual particles rather than real particles. I don't know if you're aware, but the underlying reality behind virtual photons is said to be the evanescent wave aka near field, essentially the electromagnetic field itself. So IMHO it would be reasonable to describe the gravitational field in terms of virtual particles, provided you bear in mind that these are virtual particles rather than real particles,You might want to keep in mind that QM does hypothesize a carrier particle for gravity. As I understand it however, it also lacks support in terms of LHC experimentation at the present moment however.

Belief gets kind of scarey at times. I'll read Tim's stance. Meanwhile, please don't prejudge expanding space. When you get down to the fundamentals IMHO you see that space just has to expand.I lack belief that they exist, he probably does not.

And it starts to be a stretch. Not impossible, but when you see field energy in terms of mass equivalence and hence "dark matter" you start getting other ideas.I agree. They would have to be wrong both in terms of the number and the layout as well. It would almost certainly be necessary to move the bulk of the "dark stars" (ones we cannot directly observe) to the outside edge of the galaxy and the bulk of the larger stars near the central bar.

My pleasure, again apologies for not being around. I mentioned the Lambda-CDM model, here’s what I think is wrong with it. See these two quotes:I agree. Welcome to the discussion by the way. I look forward to your input.

If you think about gravitational field energy, and energy having a mass-equivalence, it fits with the above. There might not be enough of it, but we can come back to that.

Agreed.Here is my official stance.

It is a fact that the motion of matter in the universe is observed to be significantly inconsistent with the standard physical assumptions. Therefore, the standard physical assumptions need to be either modified, or simply replaced with new assumptions.

I don't quite agree with that, because it's a concentration of energy that causes gravity. Matter causes gravity because it is a concentration of energy. I think a better assumption is that there are concentrations of energy that we haven't accounted for.There are in essence only two real candidates for new or modified assumptions: (1) There is more matter in the universe than we see, providing an unseen source for more gravity than we would have expected, or (2) The standard laws of gravity need to be modified to conform with observation.

Fair enough. We shouldn't rule out one candidate just because we favour another. For example, relic neutrinos are dark matter, and whilst they aren't massive, they are weakly interacting.Of course, both (1) & (2) could be simultaneously true. The first assumption comes in two parts: (1a) There is more ordinary (i.e., baryonic) matter than we see, and (1b) There is additional, as yet undetected nonbaryonic matter. And, of course, Both (1a) & (1b) could be simultaneously true.

With respect Tim, opinion doesn't count, and consensus doesn't count. Scientific evidence counts.In my opinion, and in the consensus opinion of the main stream science community, both (1a) & (1b) are true.

Noted. I don't see this as the central issue, so I won't dwell on it.It is known that there is more baryonic matter in the universe than previously thought, although Mozina has thus far done a poor job of finding the correct sources to justify this already mainstream conclusion.

I'd say there's an asssumption in there which essentially says "matter causes gravity". This isn't quite in line with mainstream general relativity.However, it is also known that all of this previously undetected baryonic dark matter combined falls far short of the mark required to avoid the necessity of more exotic nonbaryonic dark matter (so long as we simultaneously assume that (2) is incorrect and that the law of gravity does not need to be modified).

If it had remained undetected for a few years I'd say we should cut it some slack. But it's been decades, arguably going back to Zwicky in 1933. So I think it's only fair to challenge mainstream thinking.Hence, the bulk of mainstream research is concentrated on figuring out ways to directly or indirectly detect the nonbaryonic dark matter which has thus far remained undetected.

I see things a little differently, in some respects taking a middle path. I'd say the gravitational approaches address the energy that's there in space. It has a mass equivalence, and space is dark.However, it should also be noted that there is significant research, exemplified by numerous journal papers, devoted to (2) above, attempting to eliminate the need for any dark matter at all by modifying the laws of gravity. As far as I know, being outside my own area of expertise, these attempts have failed to find a universal solution; e.g., one form of modified gravity might work to solve "this problem" but not "that problem", and so forth, while the assumption of both baryonic, but predominately nonbaryonic dark matter produces universal solutions that simultaneously solve all of the problems (at least in principle), limited of course by observational uncertainty.

OK. I can see that a bit of an argument has brewed up here. I hope I can help you find some common ground.If Mozina thinks I am trying to "protect the status quo", or that I "insist" that some form of exotic matter must exist, then he is quite wrong, for neither of these positions he suggests are of any interest to me at all.

I'd rather say that current observation strongly suggest the presence of a non-uniform energy distribution, but they don't actually suggest that the energy is in the form of nonbaryonic dark matter particles.I do insist that the current state of observation strongly suggests the presence of nonbaryonic dark matter, and I do insist that this is in fact the simplest, most empirical, best scientific solution to the problem of conforming theory with observation, given the current state of knowledge.

OK noted.I am definitely not arguing here that the status quo must be protected from new ideas. I am simply arguing that Mozina has yet to come up with anything particularly reasonable to say about anything relating to the physical sciences in general, or the more specific sciences of cosmology & astrophysics.

Thanks for the offer, but it won't help here. We need to focus on inhomogeneous space, and then move on to an expanding universe where galaxies are gravitationally bound.Farsight, general relativity is a mathematical theory. There are some equations that define it. Those equations tell you exactly how big and what the effect of gravitational back-reaction is... and it's neither anywhere big enough nor of the right form to account for dark matter. If you want, I can teach you how to calculate that. It's not hard, but it does involve some math. If you understand Newtonian gravity and classical electrodynamics at the level of Maxwell's equations, that will suffice.

In this thread, explanations offered by knowledgeable scientists rarely help.Thanks for the offer, but it won't help here.Farsight, general relativity is a mathematical theory. There are some equations that define it. Those equations tell you exactly how big and what the effect of gravitational back-reaction is... and it's neither anywhere big enough nor of the right form to account for dark matter. If you want, I can teach you how to calculate that. It's not hard, but it does involve some math. If you understand Newtonian gravity and classical electrodynamics at the level of Maxwell's equations, that will suffice.

Alternatively, we could try to understand some simple cases before we focus on less tractable problems.We need to focus on inhomogeneous space, and then move on to an expanding universe where galaxies are gravitationally bound.

False. Although FLRW solutions (note the plural) assume the universe is homogeneous and isotropic, they allow for matter and gravity."The Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) metric is an exact solution of Einstein's field equations of general relativity; it describes a homogeneous, isotropic expanding or contracting universe..."

The first is from Einstein’s 1920 Leyden Address, where he describes a gravitational field as inhomogeneous space. The second is from the wiki FLRW page, which describes a homogeneous isotropic universe. There’s no gravity in that universe. Gravitational fields have been thrown out with the bathwater.

False. Although FLRW solutions (note the plural) assume the universe is homogeneous and isotropic, they allow for matter and gravity.

Quite right. I mean, it's a bit cheeky for that gravitational constant G to be sneaking into the solutions if there's no gravity, isn't it?

Thanks for the offer, but it won't help here. We need to focus on inhomogeneous space, and then move on to an expanding universe where galaxies are gravitationally bound.

Thanks. Sorry to have been absent for a week, I've been run off my feet.

True. It's kind of out-of-the-box exotic, but simple and obvious when you think about it.

Yes, gravitons are hypothesized, but taking the lead from QED, they would be virtual particles rather than real particles. I don't know if you're aware, but the underlying reality behind virtual photons is said to be the evanescent wave aka near field, essentially the electromagnetic field itself. So IMHO it would be reasonable to describe the gravitational field in terms of virtual particles, provided you bear in mind that these are virtual particles rather than real particles,

Belief gets kind of scarey at times. I'll read Tim's stance. Meanwhile, please don't prejudge expanding space. When you get down to the fundamentals IMHO you see that space just has to expand.

No offence, but Sol doesn't know as much as he thinks.In this thread, explanations offered by knowledgeable scientists rarely help.

This is the whole point, we have to understand the simple case first. And the simplest case is that a gravitational field is inhomogeneous space.Alternatively, we could try to understand some simple cases before we focus on less tractable problems.

I reiterate: if you assume that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic, there's absolutely no gravity in it, spacetime is flat. Now apply this to the shape of the universe and ask yourself where the curvature comes from. Pay attention to the distinction between curved space and curved spacetime.False. Although FLRW solutions (note the plural) assume the universe is homogeneous and isotropic, they allow for matter and gravity.

Lay it on me, sol. But do note that understanding the simple case relates to axioms, essentially undertstanding the terms. That's sometimes an issue.sol invictus said:That's what I'm offering to explain to you, Farsight. There's a very well-developed formalism for dealing with precisely the issue you are referring to, and it gives quantitative, definite answers. So, are you interested in learning that, or not?

Sure. I have a deep understanding of say this that gets right down to the fundamentals.sol invictus said:And do you or do you not know enough basic vector calculus to follow a simple derivation involving Newtonian gravity and a few aspects of Maxwell's equations?

I will iterate what any one who knows anything about the FLRW solutions will tell you. They include that spacetime can be curved.I reiterate: if you assume that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic, there's absolutely no gravity in it, spacetime is flat.

Now relaize that you are applying a mistake to the shape of the universe.Now apply this to the shape of the universe and ask yourself where the curvature comes from. Pay attention to the distinction between curved space and curved spacetime.

Why should he be different?No offence, but Sol doesn't know as much as he thinks.In this thread, explanations offered by knowledgeable scientists rarely help.

Empty space is the simplest case. The Schwarzschild and FLRW solutions are the simplest cases for nonempty space. The FLRW solutions are for homogeneous and isotropic (but not empty) space.This is the whole point, we have to understand the simple case first. And the simplest case is that a gravitational field is inhomogeneous space.Alternatively, we could try to understand some simple cases before we focus on less tractable problems.

Reiterate all you want, but you're wrong. This is covered in Hawking&Ellis and in standard textbooks such as those by Misner/Thorne/Wheeler or Wald.I reiterate: if you assume that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic, there's absolutely no gravity in it, spacetime is flat.False. Although FLRW solutions (note the plural) assume the universe is homogeneous and isotropic, they allow for matter and gravity.

Most things are. That's why we talk I suppose....It's a matter of perspective I suppose.

Vacuum fluctuations are real enough, as demonstrated by the Casimir effect. But that isn't what keeps the electron and proton together in a hydrogen atom. They aren't actually exchanging virtual photons. They're just the accounting units. A nice analogy is that there are no actual virtual pennies flying into your bank account when your salary gets paid in. Search google on this, but it's maybe one for another thread....Hmm. I'm not actually a big fan of the concept of 'virtual'. There are quantum mechanical kinetic energy exchanges even in a "pure vacuum". Such interactions might create localized "blips" that we think of as being "virtual" because they are short in duration, but I tend to think such kinetic energy exists in real particle form.

I skimmed the paper. I don't like it I'm afraid. Brooklyn doesn't expand for the same reason a galaxy doesn't expand or an electron doesn't expand, because it's "bound". The simple analogy is that of the rubber-sheet universe with a knot in it. Stretch it and the knot doesn't expand with the rubber sheet. But the paper treats space as absolutely empty. That isn't in line with Einstein's Leyden address, where he talked of inhomogeneous space and said has, I think, finally disposed of the view that space is physically empty. Space isn't the same as nothing, it sustains fields and waves, from which we can make matter via pair production. There's energy in it, that energy has a mass equivalence, the vacuum isn't the same as nothing. This touches on what I mentioned earlier about space just having to expand. The universe as a whole is not bound, and there's stress-energy in the space, even in an "empty model". Stress is measured in Pascals like pressure, the dimensionality of energy is pressure x volume, so the universe starts with a high spatial energy density, like a high pressure, and there's nothing to confine it or bind it, and it just has to expand. So switch from the rubber-sheet analogy to a stress-ball universe. Squeeze it in your fist and let it go.I don't have any trouble with the concept of "spacetime" expansion in the sense that objects in motion stay in motion and over time the objects themselves will expand. It's more the notion that "space" expands that I have a problem with. This paper probably best explains my doubts about the concept of "space expansion":

http://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0601171

I'm more inclined to believe it's a function of time dilation than a function of space expansion.

Yep, it's an interesting one for all sorts of reasons. Like this: neutrinos are more like photons than electrons.I'm also intrigued by the (remote) possibility the neutrinos might actually travel a wee bit faster than C. That could (probably will) turn out to be an anomaly, but it does raise some interesting possibilities if it holds up.

They're probably expert in the MTW version, which is subtly different to Einstein's original. Have a look at Golden age of general relativity and note the paradigm shifts. One was the big bang, which I'm happy with. Another is the role of curvature in general relativity, which I'm not. I think it causes problems for cosmologists.FYI, sol, edd and several others engaged in this thread are EXCELLENT sources of information related to GR theory. I'm sure they can answer any questions you might have about that topic.

A concentration of energy results in curved spacetime. This energy has a mass equivalence. Matter exhibits the property of mass but mass doesn't cause spacetime curvature, so much as the energy content of matter. Now go back to that Einstein quote where he referred to a gravitational field as inhomogeneous space, understand that if the energy distribution is absolutely uniform, space is homogeneous, there's no gravitational field, spacetime is flat, and light travels in straight lines.RealityCheck said:...The curvature of spacetime comes from the mass and energy inside the universe.

But there is such a thing as curved space, and it is very different to curved spacetime.Pay attention to that there is no such thing as 'curved space' in GR. Space is always part of spacetime.

Don't bible-thump at me, Clinger. Give a counter-argument if you like, and yes include references, but base it on evidence and logic and solid points of discussion....Reiterate all you want, but you're wrong. This is covered in Hawking&Ellis and in standard textbooks such as those by Misner/Thorne/Wheeler or Wald.

In actual fact it is the other way around.Yep, it's an interesting one for all sorts of reasons. Like this: neutrinos are more like photons than electrons.

What is so special about Einstein's original version?They're probably expert in the MTW version, which is subtly different to Einstein's original.

Why are you not happy with the fact that people have grown to appreciate the importance of spacetime curvature in GR?Have a look at Golden age of general relativity and note the paradigm shifts. One was the big bang, which I'm happy with. Another is the role of curvature in general relativity, which I'm not. I think it causes problems for cosmologists.

Yep, it's an interesting one for all sorts of reasons. Like this: neutrinos are more like photons than electrons.

Wrong: Any mass or energy results in curved spacetime.A concentration of energy results in curved spacetime.

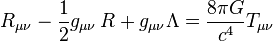

The left hand side is the geometry of spacetime.The Einstein field equations (EFE) may be written in the form:[1]

where is the Ricci curvature tensor,

is the Ricci curvature tensor, the scalar curvature,

the scalar curvature, the metric tensor,

the metric tensor, is the cosmological constant,

is the cosmological constant, is Newton's gravitational constant,

is Newton's gravitational constant, the speed of light, and

the speed of light, and the stress-energy tensor.

the stress-energy tensor.

is the density of relativistic mass.

Clicking on the link above reveals a post in which I didn't write those two sentences you attributed to me.But there is such a thing as curved space, and it is very different to curved spacetime.Pay attention to that there is no such thing as 'curved space' in GR. Space is always part of spacetime.

The evidence of your recent posts shows you are misrepresenting the FLRW solutions. That fact can be checked by anyone who has access to the standard references I cited. If you believe those standard references are incorrect on this point, it's your responsibility to explain why they're wrong and you're right.Don't bible-thump at me, Clinger. Give a counter-argument if you like, and yes include references, but base it on evidence and logic and solid points of discussion....Reiterate all you want, but you're wrong. This is covered in Hawking&Ellis and in standard textbooks such as those by Misner/Thorne/Wheeler or Wald.

Quite right. I mean, it's a bit cheeky for that gravitational constant G to be sneaking into the solutions if there's no gravity, isn't it?