What you seem to not understand, ufology, is that the skeptics here don't really personally care whether the particular object in question was a cloud or an aircraft, apart from what the objective facts can tell us about what is most likely the truth of the matter.

Although some of us happen to be just as geeky as anyone about our enthusiasm for odd and experimental aircraft, we're not particularly interested in establishing that a YB-49 might have been serviceable and airborne over the Pacific Ocean in the evening of December 16, 1953. Though it would certainly be cool if there were lots of exotic Northrup YB-49 bombers buzzing around the skies in the mid-1950s, we set aside those emotions when it comes to doing research because we're not doing this for the purpose of bolstering our own fantasies; we're here to determine the objective facts.

To that end, it's all about the process by which we arrive at our conclusions. That process is

everything when it comes to trying to determine the objective reality of a situation. That process means reserving our conclusion while conducting our investigation.

For example, refraining from presumptuously referring to the

unidentified object as "the flying wing" or "a lenticular cloud" during our analysis, until we have reliably established that conclusion by means of the objective evidence. That's precisely why the acronym "UFO" was initially created by the USAF: specifically to reference objects seen in the sky which have not been positively identified.

Investigation follows a defined procedure:

- Gathering evidence like eyewitness accounts, maps, verifiable facts, weather data, mathematics (in this case, geometry/trigonometry), relevant scientific knowledge (physics, meteorology), etc.

- Dispassionately examining and weighing the evidence according to reliability and completeness. In terms of reliability, objective evidence like maps, verifiable facts, mathematics, the laws of physics, etc. will always take precedent over less reliable subjective claims such as eyewitness accounts, especially when multiple accounts are contradictory of one another.

Of paramount importance is the realization that eyewitness accounts do not represent evidence for themselves, only evidence that somebody at some point claimed something. Thus, eyewitness accounts are only useful insofar as they might provide leads for further investigation.

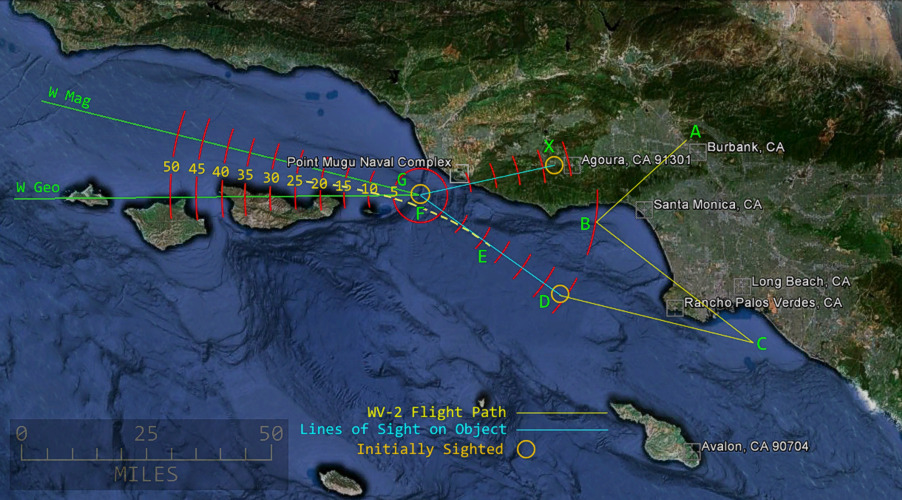

- Constructing a model based on the evidence that accounts for as much of the evidence as possible. In this case, the "model" was Stray Cat's maps with the sight-lines of the observers.

- Proposing hypotheses that fit the evidence.

- Testing those hypotheses against the model, and seeking out additional evidence if any unsupported assumptions have been made by any hypothesis.

- Eliminating hypotheses that don't fit the model, that contradict the evidence, or that require assumptions unsubstantiated by evidence (a.k.a. "Occam's Razor").

- Finally deciding on the most reasonable conclusion that fits as much of the evidence as possible, and eliminates or accounts for any contradictions in the evidence.

As others have pointed out, from the researcher's point of view,

the procedure must be considered more important than the actual conclusion, because the adherence to proper procedure is the most certain way to reach an accurate conclusion. The more the researcher allows his preferred conclusion to influence his methodology, the more confirmation bias is introduced and the less accurate the conclusion is likely to be.