What this illustrates is that Mr tfk is kinda faking it and doesn't understand the design strategy of the engineers.

You really sure you want to go down this path, JS?

And just when I was about to say that you got an engineering point correct, for a change.

If one were to tally up all the things that you’ve asserted that were incorrect, it’d be a fairly long list. And, from that list, it’d become clear, pretty damn fast, that you’re in no position to talk about “the design strategy of the engineers”.

And you’re wrong about your assertion that the hat truss was not an important component of reducing wind sway in the tower. As I’ll show below.

And you were COMPLETELY wrong about the main topic about that post: Whether or not the hat truss could redistribute loads between the core & external columns.

The NIST report was extremely clear load redistribution between the core & external columns,

as a direct result of the hat truss, was one of the key factors in the collapse of the towers.

__

But first, what you got right…

What you got correct was that the columns above the severed columns were NOT “hanging by the hat truss”, as asserted by JD & Oz.

This fact is shown in this figure:

Fig 3-23 of NCSTAR1-6D

The vierendeel action of the spandrel plates & external columns supported (thru shear in the spandrels) the fractured columns above the breaks, and routed the load that those columns had carried around the hole in the wall.

But one can see from the graph above that those columns were still in lots of compression. If they were “hanging from the hat truss”, as JD & Oz asserted, then the loads in them would have been tensile, not compressive.

Now, as for this one…

The hat truss was designed to spread the loads of antennas to be built on the towers. THAT was the primary purpose.

Which is exactly what I meant when I wrote:

tfk said:

A 2nd purpose was to provide a strong, moment resisting base for the towers on top, of course.

I could have been more clear by writing “… a strong, moment resisting base for the antenna towers on top …”.

James Glanz’ “City in the Sky” gives additional details on the origins of, and purpose for, the hat truss.

And here is the passage.

City In The Sky said:

Even the dampers would not be enough [to reduce the wind sway. -tk]. Robertson and John Skilling had to go to Yamasaki and tell him that all of the experimental data they had been collecting indicated that the towers would still sway too much unless three separate structural modifications were carried out.

… he would have to widen Yamasaki’s pinstripe columns slightly to make them stiffer.

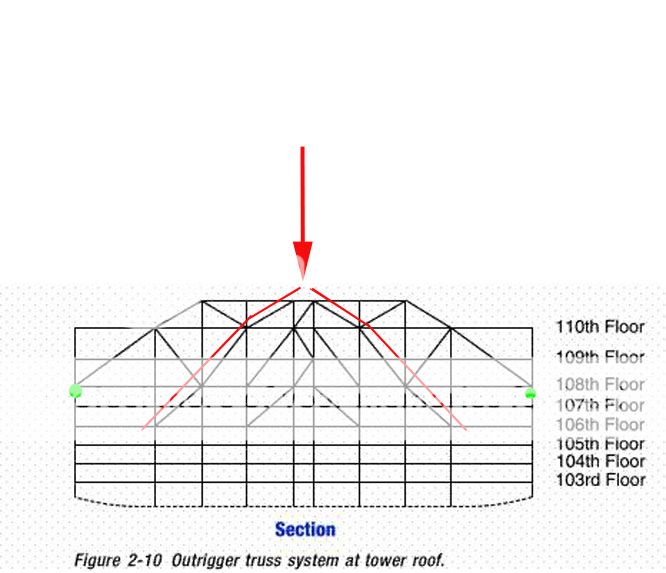

… There was more, Robertson said. Still another element of his solution was a huge support structure called a hat truss that would sit atop each building and tie its core to its exterior. Already under discussion as a brace to hold up a soaring TV antenna on the north tower, the hat truss could add robustness to the entire building from top to bottom, Robertson knew, with a few tweaks in the design.

… And finally, Robertson wanted to twist the orientation of the rectangular core— containing interior structural columns, fire stairwells, and elevators— in one of the towers.

So, yes, JS, the hat truss was absolutely an important component that reduced the amount of sway for a given amount of wind.

If you understood structural mechanics & stress distribution in cantilevers, you’d realize that the hat truss HAD to have a dramatic effect on the amount of deflection for a given wind load.

The composite floors act as strong shear-resisting membranes against deformations within the 2D axis of the floor.

But they (& their connections) are lousy at resisting “out of plane shear”. This means that the core can move up or down with respect to the peripheral columns, and the floors will simply deflect.

If I had a cantilevered rectangular inner box tube & a square outer box tube, fixed at one end and free at the other, connected by thin membranes along their length (i.e., a model for the towers without a hat truss), then when I applied a lateral load to the assembly, the top of the inner tube could rise above top of the outer tube, as well as have a differing deflection angle at the top.

If I were to then fix (vertically, horizontally & angularly) the top of the two tubes together (i.e., adding a hat truss), then the whole assembly becomes MUCH stiffer, because the two tubes cannot move & rotate independently of each other, and you’ve added multiple constraints regarding their vertical position & terminal angles of deflection.

The hat truss ties together the core columns with the external columns, adding a very important, very strong constraints on their relative motion & deflections. The simple fact that, when the assembly is deflected, there will be large stresses contained within the hat truss itself, as well as increased stresses within the core & external columns tells you, via Castigliano’s Theorem, that the whole assembly has to be much stiffer.

It was not meant to redistribute loads... it was not designed to resist wind shear.

Wrong.

See above.

Your own reference says, “This truss system allowed some load redistribution between the perimeter and core columns”.

And NIST elaborates on the important consequences of the load redistribution that DID happen, during the time between impact & collapse initiation, in extensive detail, in NCSTAR1-6D.

PS.

Hopefully he might have learned a thing of two from a dumb architect.

Perhaps surprisingly, ...

... no comment.